The new commodity superpowers

In the first part of a series, countries that produce the metals central to the energy transition want to rewrite the rules of mineral extraction

By

Leslie Hook in London,

Harry Dempsey in Lualaba Province, and

Ciara Nugent in Buenos Aires

August 8 2023

The red-brown landscape of Tenke-Fungurume, one of the world’s largest copper and cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, is covered by tens of thousands of dusty sacks.The bags stacked up by the roadside and piled next to buildings contain a stash of cobalt hydroxide powder equivalent to almost a tenth of the world’s annual consumption — and worth about half a billion dollars.

The haphazard stockpiles of this bright green powder, a key ingredient in electric car batteries, point to how the DRC, the world’s largest producer of cobalt, is starting to flex its muscles when it comes to the metals needed for the energy transition.CMOC, the Chinese operator of the Tenke-Fungurume mine, agreed in April to pay $800mn to the government to settle a tax dispute which had seen the company slapped with an export ban for the previous 10 months.

And now the DRC government is undertaking a sweeping review of all its mining joint ventures with foreign investors. “We’re not satisfied. None of these contracts create value for us,” says Guy Robert Lukama, head of the DRC’s state-owned mining company Gécamines. He would like to see more jobs, revenue and higher-value mineral activities captured by the DRC.

At the entrance to his office, a cabinet display of highly mineralised rocks makes his point about the riches on offer. Lukama also advocates government intervention to keep cobalt prices high: “Excess of supply needs to be organised properly. Some export quotas will be useful,” he says.

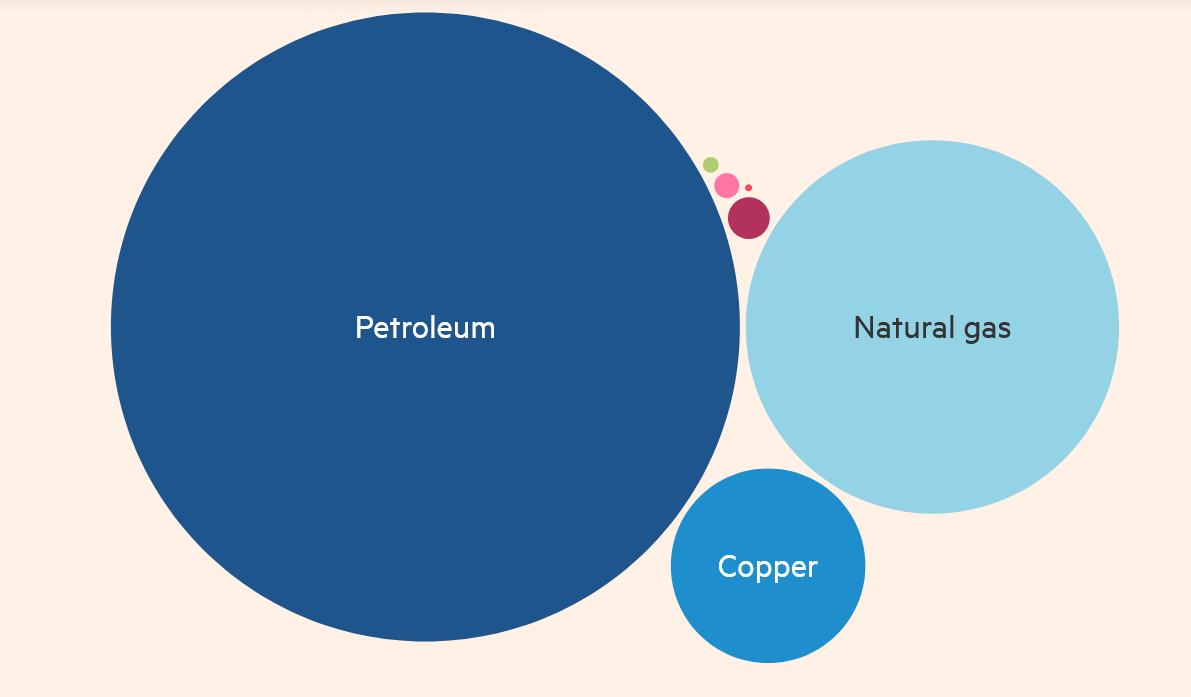

The DRC is far from alone. As the world moves from an energy system built on fossil fuels to one powered by electricity and renewables, global demand for materials such as copper, cobalt, nickel and lithium is transforming the fortunes of the countries that produce them.

The mining of certain metals is highly concentrated among just a few countries. For cobalt, the DRC accounts for 70 per cent of global mining. In nickel, the top three producers (Indonesia, the Philippines and Russia) account for two-thirds of the market. While for lithium, the top three producers (Australia, Chile and China) account for more than 90 per cent.

Demand is only going to grow in coming years. Under current plans, none of these key commodities will have enough operating mines by 2030 to build the infrastructure necessary to limit global warming to 1.5C above preindustrial levels, according to the International Energy Agency.By the end of this decade, the nascent lithium market needs to triple in size, while copper supply will be short by 2.4mn tonnes, it says.

The growing demand for these commodities is starting to shake up both the economics and the geopolitics of the energy world.

The supply chains for some of these metals are becoming entangled in the rising tensions between the west and China, which dominates processing capacity for lithium, cobalt and rare earths and is considering restricting exports of some materials. Governments from Washington to Brussels to Tokyo are assessing where they can reliably source critical minerals without going through Beijing’s orbit.

This shift is also transforming some smaller and historically under-developed countries into commodity superpowers. And their governments are now intent on rewriting the rules of mineral extraction.

Many are trying to capture more of the value of their minerals, by doing more processing and value-added manufacturing domestically. Some are also attempting to control the supply, by nationalising mineral resources, introducing export controls, and even proposing cartels.

Where once some of these resource-rich countries were victims of exploitation that can date back to colonial times, now they are becoming empowered to take back control of their fates.

Just in the past 12 months, Zimbabwe and Namibia banned exports of raw lithium; Chile increased state control over lithium mining; while Mexico plunged its nascent lithium industry into uncertainty with a new review of mining concessions.

Meanwhile, Indonesia added export controls on bauxite (a key ingredient in aluminium) to its pre-existing ban on exports of raw nickel ore.“Every government will seek a deal with the mining industry that’s a fair one, that is a winner for the country and the winner for the industry,” says Jakob Stausholm, chief executive of Rio Tinto, which has itself recently been to the negotiating table in Chile and in Mongolia.

While he dismisses the idea that rising “nationalism” is behind this, he does acknowledge there has been a change. “It’s probably going to be more and more difficult just to mine and extract and export; very often a nation wants to have some processing facilities associated with the mining.

”The subtle shift in power towards the producers of sought-after battery metals is similar to other commodities shifts of the past, like the rise of coal during 19th century or the rise of tin during the 20th. But how far will producers go to take advantage of this moment? And how long can they make it last?

Indonesia’s opportunity

The poster child for harnessing value from materials is Indonesia, which produces nearly half of the world’s nickel, a key ingredient in electric car batteries.

Years of export controls on raw nickel have already succeeded in building an extensive domestic smelting industry, as well as battery plants and several electric vehicle factories. After the country banned exports of raw nickel in 2014, it attracted more than $15bn of foreign investment in nickel processing, primarily from China.

Today Indonesia has banned exports of everything from nickel ore to bauxite, with an export ban on copper concentrate coming into effect next year.Not everyone agrees with these policies, however: the EU has challenged them at the World Trade Organization and won an initial hearing. Indonesia is appealing against the verdict.

But government officials say the country’s efforts to build domestic industry and encourage manufacturing are straight from the same playbook that western countries used a century ago.

“This is not something we are doing out of the blue,” says Investment Minister Bahlil Lahadalia. “We are learning from our developed country counterparts, who in the past have resorted to these unorthodox policies.”

He points to the way the UK banned exports of raw wool during the 16th century, to stimulate its domestic textile industry. Or the US, which used high import taxes during the 19th and 20th centuries to encourage more manufacturing to take place domestically.

Lahadalia wants to take things one step further, by creating an Opec-style cartel to keep prices high for nickel and other battery materials. “Indonesia is studying the possibility to form a similar governance structure [to Opec] with regard to the minerals we have,” he says.

Whether or not that happens, the rise of nickel has certainly given Indonesia a higher profile. When President Joko Widodo, or “Jokowi” as he is typically known, visited the US last year, he met both President Joe Biden in Washington and Tesla CEO Elon Musk in an out-of-the way stopover in Boca Chica, Texas.

Jokowi later said he encouraged Musk to build Tesla’s entire supply chain in the country, “from upstream to downstream.”

Window of opportunity

Not every country will follow the same trajectory as Indonesia, however.A new report from the International Renewable Energy Agency finds that metals producers will be able to wield influence in the short term, while production is concentrated and demand is growing, but they are unlikely to have the kind of lasting geopolitical power enjoyed by oil and gas producers.

One challenge is that battery metals like lithium are well distributed around the globe — at least in terms of geological reserves, if not in actual mine production. Today’s high lithium prices are making it efficient to develop deposits that were previously too expensive to access, and fuelling the broader expansion of hard-rock lithium mining in places like China and Australia.

An example of how mineral production can shift is lithium mining in South America. Chile is today the region’s dominant producer, but neighbouring Argentina, which has more business-friendly mining policies, could eventually overtake it.

Argentina’s 23 provinces control their own natural resources and have enthusiastically courted mining business. With roughly $9.6bn of lithium investment announced in the past three years, and 38 projects in the pipeline, officials say Argentina’s production should go up six-fold over the next five years.“Investment in lithium has never stopped and I think that has to do with the fact that we are open to private investment, and with uncertainty about the policies being rolled out in other countries,” says Fernanda Ávila, Argentina’s mining minister.

Argentina’s position as an anomaly among South American lithium-holding countries has helped it attract investment, even as it has dried up in other sectors of the economy amid triple-digit inflation. While some politicians in South America’s “lithium triangle” — Chile, Argentina and Bolivia — have floated the idea of an Opec-style lithium cartel, Ávila is less than enthusiastic about the idea.

Although “we have a very good relationship with our neighbouring countries”, she says, “that’s not a topic that’s on the agenda.”This is another reason why producing battery metals is different from producing oil: it is very hard to form a successful cartel.

During the 20th century, several key commodities were controlled by cartels. Tin was managed through the International Tin Council from the 1950s to the 1980s — and Indonesia, Bolivia and the then Belgian Congo were all producer members. Likewise coffee producers banded together in a cartel during the 1960s and ‘70s; and natural rubber producers maintained a cartel until the 1990s.

John Baffes, head of the Commodities Unit at the World Bank, who has studied these groups, says successful cartels have three characteristics: a small number of producers, who share a well-defined objective, over a short timetable.

He thinks it will be difficult for battery metals producers to form cartels. “You may have some countries that come together, to create an environment that may be beneficial for them, such as keeping prices high,” says Baffes. “But that will be the seeds of failure, because more entities will come in, from outside of the group.”

Chart showing Critical mineral production is highly concentrated in a handful of large multinationals and state-owned enterprises – Market share of select materials, 2021 (%) cobalt, platinum, nickel and lithium

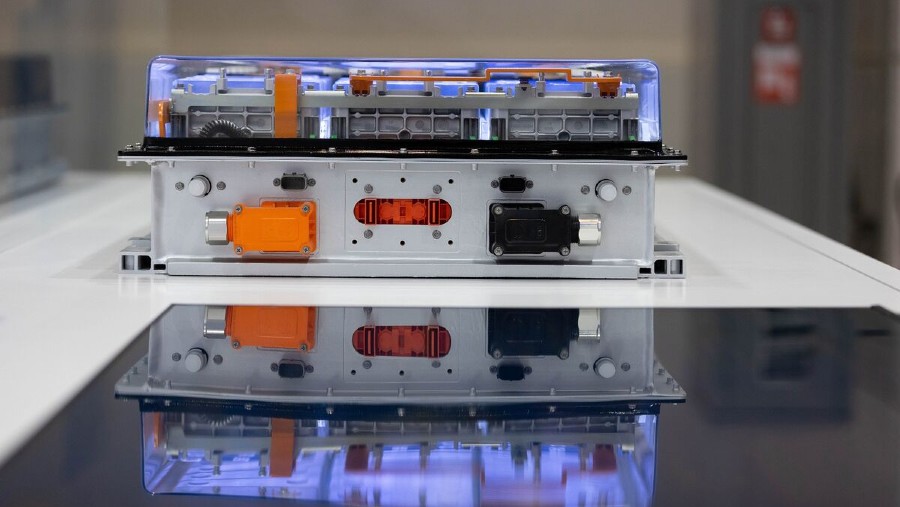

The speed at which battery technologies are evolving, and their ingredients changing, could also undercut efforts at cartelisation.Unlike oil, which is very hard to replace as a fuel source, battery metals have a much higher risk of substitution. The laboratories developing new battery chemistries are constantly evolving their formulas to use less of the metals that are expensive or hard to acquire.This is already starting to happen with cobalt, which carmakers are trying to reduce in their batteries due to its high cost, as well as concerns about human rights in the DRC.

In a cautionary tale of how quickly the demand outlook can change, the use of cobalt-free batteries in China has surged from 18 per cent of the EV market in 2020, to 60 per cent this year, according to Rho Motion, an EV consultancy. Manganese-rich batteries are also on the horizon, which could further reduce cobalt use.

“One of the consequences of the rise in non-cobalt batteries is that shortages previously forecast for cobalt for around 2024 and 2025 may not materialise,” says Andries Gerbens, a trader at Darton Commodities. “It may suggest cobalt prices remain lower.”The recent fall in prices of cobalt, nickel and lithium could damp efforts by producer countries to extract more rent and build up domestic manufacturing. After cobalt and lithium experienced a huge price rally in 2021 and 2022, driven primarily by demand from electric vehicle batteries, the market this year has been much calmer.

A slowdown in China’s production of electric vehicles, combined with an increase in production of cobalt hydroxide and lithium carbonate, has brought their prices down 30 per cent and 40 per cent, respectively, during the first six months of the year, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Veteran miners say this cycle has played out many times before. Resource nationalism tends to increase when commodity prices are high, or when elections are approaching, says Mick Davis, founder of Vision Blue Resources and former chief executive of Xstrata.

During these times, “[politicians] inevitably try to capture more of the rent than they initially envisioned and agreed,” says Davis. “The result always ends in tears. It means that the development of their mineral resources takes longer and longer to happen.”

Carpe diem

Yet while the cycle still allows producer countries to flex their powers, they are intent on seizing the moment however they can.Earlier this year Chile, the world’s second-largest lithium producer, announced a plan to semi-nationalise the industry: it will give greater control of two giant lithium mines in the Atacama Desert to a state mining company when the current contracts end in 2030 and 2043, with both those projects and all future ones becoming public-private partnerships.Chilean President Gabriel Boric said the plan to increase state control of lithium is the best chance Chile has to become a “developed economy” and to distribute wealth in a more just way. “No more ‘mining for the few’.

We have to find a way to share the benefits of our country among all Chileans,” he said. And many producers are succeeding in taking steps up the value chain, in a bid to create sustainable economic growth. In the DRC, construction of the country’s second copper smelter is under way near the Kamoa-Kakula copper mine.

Chile, meanwhile, is offering preferential prices on lithium carbonate to companies who set up value-added lithium projects in the country. The first taker is China’s BYD, one of the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturers, which announced in April that it would build a lithium cathode factory in northern Chile, with 500 jobs expected in the investment phase.Argentina is set to open a small lithium ion battery factory — Latin America’s first — in September, with a larger plant to follow next year.

Owned by state energy research company Y-TEC, the plant in the province of Buenos Aires will use lithium mined in Argentina by US firm Livent to produce the equivalent of 400 EV batteries a year.

Indonesia’s attempts to build out an electric vehicle industry are bearing fruit at an even larger scale. Earlier this year, Ford announced an investment in a multibillion-dollar nickel processing facility. This summer, Hyundai broke ground on a battery plant, its second manufacturing facility in the country.

As the energy transition starts to recast the systems of power and wealth that dominated the 20th century, the new battery metals producers are just getting started. Many see this shift in the power dynamic as a welcome change.

“It is absolutely essential that we rewrite the legacy of the mining industry, so that mineral rich countries can capture more of the economic value,” says Elizabeth Press, director of planning at Irena, and author of the report on critical minerals. “We see a greater awareness from both sides that things cannot continue as they were.”

In the first part of a series, countries that produce the metals central to the energy transition want to rewrite the rules of mineral extraction

www.ft.com