Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Covid-19 News and Discussions

- Thread starter Yommie

- Start date

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #214

Free supply of COVID-19 tests coming to an end in Saskatchewan

Rapid antigen tests will still be available while supplies last and then remain available for purchase at some retailers.

Free supply of COVID-19 tests coming to an end in Saskatchewan

Rapid antigen tests will still be available at local distribution centres while supplies last.Author of the article:

Regina Leader-Post

Published Feb 14, 2024 • 1 minute read

Join the conversation

Article content

With the start of the COVID-19 pandemic nearly four years in the rear-view, measures like masks, social distancing and free COVID-19 test kits have continued to wind down.On Wednesday, the Government of Saskatchewan confirmed it will no longer supply free tests, which have been widely available at voluntary distribution sites like public libraries.

Article content

In response to the pandemic, the federal government procured and distributed rapid antigen tests to provinces and territories, making them freely available to individuals and families as a way to prevent the spread of the COVID-19.

Advertisement 2

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

TRENDING

Letter: Melting glaciers threaten Sask. River, Saskatoon water supply

Two Saskatoon vehicles retrieved, drivers face multiple charges

Phil Tank: Sask. Party has itself to blame for plummeting popularity

Opinion: Saskatchewan should view education spending as investment

Saskatoon man who stabbed nightclub patrons helped convict a child sex offender

“The program was completed at the end of 2022 when the last of the federally-supplied tests were sent to provinces,” said a statement from the Ministry of Health on Wednesday. “Saskatchewan has made every effort to use this stock responsibly by making the tests widely available to the public through more than 600 partnering distribution sites.”

In November 2022, the province said it had no “current” plan to end distribution as the federal prepared to stop regular supply of rapid test kits in 2023. The government said it would keep a reserve that may be used “in the case of potential resurgence of COVID-19.”

The province says that remaining test kits will continue to be available at public distribution locations across Saskatchewan while supplies last, but the tests that are still available will largely expire in March 2024.

In an Instagram post Tuesday, the Regina Public Library said test kits will remain available at all locations while supplies last.

The ministry of health said Rapid Antigen Tests for COVID-19 are still available for purchase from retailers, as they have been since demand for tests first emerged.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #215

There’s a New Life-Saving Vaccine. Why Won’t People Take It?

The next front in disinformation and the vaccine wars.

There’s a New Life-Saving Vaccine. Why Won’t People Take It?

The next front in disinformation and the vaccine wars.

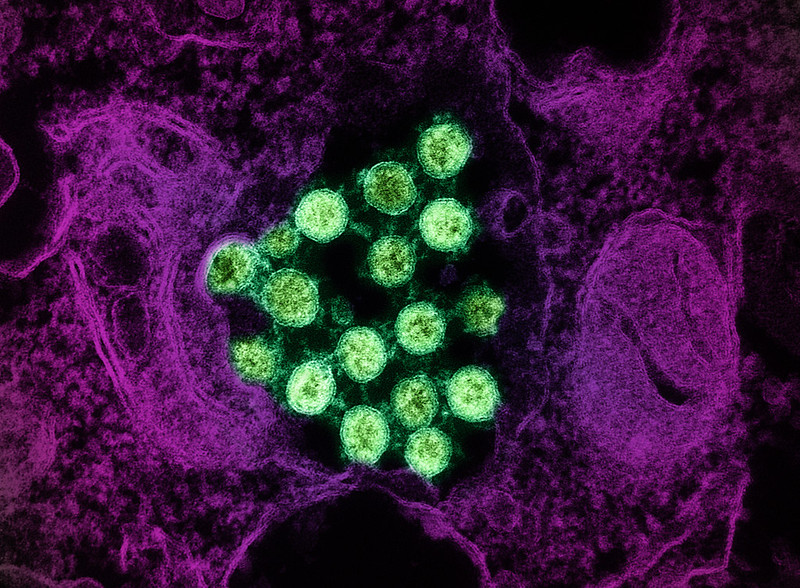

"The science of countering misinformation is still young," writes Joanne Kenen. | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH via AP

By JOANNE KENEN

02/13/2024 05:00 AM EST

Florence Rosen, a newly minted grandma and semi-retired pediatrician, recently added a new line to her resume: social media influencer.

Rosen, who often films herself with her baby grandson snuggled against her shoulder, is among a contingent of “TikTok Docs” — and nurses — who have taken to the fast-growing social media video platform to try to talk Americans down from the vaccine-fearing ledge.

“Do I think this vaccine is great? I do,” she exclaims to her more than 158,000 followers. It’s an “absolutely wonderful thing,” and yes, she says, she’s gotten it herself.

But she’s not talking about the Covid vaccine. She’s praising a new shot against RSV.

RSV, or respiratory syncytial virus, usually hits in fall and winter. It’s mild for most people but lethal for some — especially babies and older people. In a typical year, according to the CDC, as many as 80,000 children under age 5 are hospitalized, and between 100 and 300 kids die. For those 65 and over, there are up to 160,000 hospitalizations a year, and 6,000 to 10,000 deaths.

But ahead of this RSV season, for the first time ever, immunization was finally approved for the most vulnerable groups of Americans, young and old. It was also recommended for those late in pregnancy, which would protect infants from birth.

Would people get the jab? As this RSV season winds down, the answer is that by and large, they did not.

The latest data from the CDC shows that only 16 percent of eligible pregnant people got vaccinated. Among the over 60 population, it was just over one in five. And among babies and eligible young children, the uptake was “low,” the CDC said.

Four years after Covid hit and fueled growing vaccine hesitancy, the rollout of the RSV vaccine this fall and winter offered a case study unfolding in real time. At issue was whether the public health and medical communities had acquired the skills, speed and agility needed to counter malicious misinformation before it took hold in the public’s mind.

Becerra criticizes Covid disinformation campaigns

Share

Play Video

A series of organizations and strategies sprang up, both online and off, to debunk misinformation or “prebunk” it or tackle it in some other way. The action has not just been on TikTok but on WhatsApp, Google and in local communities across the country. But it hasn’t been enough to rebuild trust among an increasingly skeptical nation, particularly on a new vaccine against an old disease.

“If the question is, is the public health community better prepared than it was three years ago? I can answer yes,” said Ashish Jha, back at his post as dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health after serving for a year as the Biden administration’s Covid response coordinator.

MOST READ

Chief justice gives Jack Smith one week to respond to Trump’s bid to stave off trial

Get Used to It: Biden Isn’t Going Anywhere

After facing off with Senate ‘Freedom Caucus,’ McConnell urges Johnson on Ukraine

Why John Bolton Is Certain Trump Really Wants to Blow Up NATO

Democrats win back George Santos seat in hotly contested election

But, Jha added, doctors, nurses, public health officers and government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control, are operating in a challenging environment where too many downplay the winter respiratory season. These “minimizers” don’t acknowledge just how lethal such diseases, including RSV, can be for the high-risk population, adding, “It’s been very hard to break through that wall of bad information.”

The science of countering misinformation is still young.

All sorts of strategies that would seem to be potent turn out not to persuade people — or they do, but the effect is ephemeral, with people reverting to their original false beliefs in as little as a week.

Still, health organizations have begun to mobilize since the tidal wave of Covid vaccine misinformation undermined demand for the shots and drove broader suspicion toward all vaccines, including routine childhood immunization for diseases like measles. But while clinicians and health groups are more alert to the threats, much of the population is so distrustful of public health and medicine — inside or outside of government — that any assertions of safety immediately get sucked into the conspiracy vortex.

The attack against RSV immunization during this first season wasn’t at Covid vaccine proportions, but it is out there.

“Despite 12 Deaths During Clinical Trials, CDC Signs Off on RSV Shots for Newborns,” read an alert from the Children’s Health Defense, the anti-vaccine group founded by independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. In fact, none of those deaths were caused by the shots, and there is ample data about their safety, including during pregnancy.

That didn’t stop another vaccine critic physician named Peter McCullough from urging his 979,500 followers on X (the site formerly known as Twitter) not to get vaccinated. “RSV in infancy easy to treat with nebulizers,” he claimed. And there were others like him on various social media platforms.

“If the question is, is the public health community better prepared than it was three years ago? I can answer yes,” said Ashish Jha. | Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Many people have been seeking out information on RSV, according to the Public Health Communications Collaborative, which was formed by the CDC Foundation, the de Beaumont Foundation and Trust for America’s Health in 2020. The organization, which brought in additional partners, works to provide accurate and effective messaging to the public health community and tracks online trends. It has found that when people search online for information on RSV, they see both facts and false claims. And for many people, after the last few years of competing online claims, it can be hard to figure out which is which.

In one major victory for accuracy and the public health world, Google followed guidance from experts convened under the National Academy of Medicine and the World Health Organization. Those experts outlined how tech platforms can identify credible sources of health information that can be elevated online. It’s not that nothing wrong or nefarious about RSV or any other health topic will ever get through Google search or YouTube, but these practices may make it less pervasive. For instance, if you google “RSV,” the first items that appear on the screen come from sources like the CDC, the Mayo Clinic, the American Lung Association — not from some self-appointed vaccine “expert” posting jeremiads about fictitious vaccine hazards from his basement.

“What we did was give [Google] a rubric and a blueprint to help them justify elevating credible sources,” said Antonia Villarruel, the dean of the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing and a co-author of the credible sources report. “You get fact-based information as the first component” of a search.

Still, there are plenty of other online venues where misinformation metastasizes.

“Once these beliefs have taken root, it’s harder to disabuse people of them,” said Richard Baron, the president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine, which has a foundation that has spent the last few years looking at misinformation and distrust in medicine. “And citing the FDA and CDC doesn’t work for people who believe the narrative that the FDA and the government that’s supposed to protect us is either captured by industry or in on the game.”

It’s hard to combat falsehoods that play on fear and distrust and division. Researchers have found that fact-checking — also known as debunking — is helpful for reaching those people who are uncertain or worried, who need more information but aren’t adamantly opposed to vaccines. Many of the people who started out hesitant about the Covid vaccine did end up getting it, an outcome that reflected both mandates and growing confidence in the safety as more people took the shots.

But debunking doesn’t work so well on people who are dug in. Plus, by the time something gets fact-checked or debunked, it’s already circulating and has taken hold among some parts of the population.

That’s given rise to an effort to “prebunk,” or try to get ahead of the misinformation. Sometimes efforts are broad and largely intended to educate people (sometimes through quick online games such as the Bad News game or Go Viral) so their emotions and fears aren’t so easily manipulated on social media. It turns out we are hard-wired in ways that make it easier to petrify than to reassure.

The second kind of prebunking aims at either anticipating misinformation or at least detecting it so quickly that the public health community can counter it before it explodes.

With vaccines, it’s possible to prebunk and blunt some of the predictable tropes since there’s a well-known anti-vax playbook of falsehoods. The various fictions include: Vaccines haven’t been thoroughly tested or they cause autism or they change human DNA or the side effects are worse than the disease or the vaccine gives you the disease or “natural” products boost immunity better than vaccines or vaccines are just a way for Big Pharma to make more money or vaccines damage fertility. (That last one is a particularly pernicious message given that the RSV vaccine is given during pregnancy.)

Those messages persist and proliferate, despite years of accelerating efforts to swat them down. And not all negative messaging can be anticipated. Did anyone really foresee that meme about Bill Gates inserting microchips in us via Covid vaccines? How about that wild claim that Covid vaccines contain eggs that hatch synthetic parasites that thrive inside the human body?

In other words, prebunking may work up to a point against predictable messages, but public health and medicine need a way of monitoring social media to rapidly identify newly emerging misinformation. The right messages — say from trusted public figures who talk about why they are getting a certain vaccine or are giving it to their child — need to get out fast.

“Then you begin to build the confidence so that when that one crazy story comes in, it doesn’t have the same impact,” said Jha.

Several efforts to develop that kind of agility are emerging.

Among the most comprehensive is the initiative from the Public Health Communications Collaborative, which partners with the Public Good Projects, a health care nonprofit that does broad, rapid monitoring of social media and works with both influencers and public health organizations.

The Public Good Projects shares with clinicians, public health officials and others a monthly survey of the health disinformation landscape. But monthly isn’t good enough when lies zip around the world in seconds. So Public Good now does more real-time monitoring, and when something bubbles up, the Collaborative shares it with health departments and agencies across the country — about 30,000 people as of late autumn, each of whom has their own networks. The Collaborative also sends out best practices for fighting high-risk misinformation, without inadvertently amplifying falsehoods.

If the Collaborative is working on the public health side, another new initiative called Coalition for Trust in Health and Science is bringing together a large and growing group of public, private and nonprofit health organizations — medical, clinician, science and health care industry groups along with more traditional public health organizations.

“Given the magnitude of the challenge of misinformation/disinformation and distrust … we felt like this would be the moment where you had to bring together the entire health ecosystem,” said one of the founders, Reed Tuckson a well-known health consultant and physician who is also a co-founder of Black Coalition Against Covid. The organization, though drawing in a broad membership, is still in the early stages.

Other advocates have developed more ad hoc approaches.

A group called ThisIsOurShot and its sister site VacunateYa, organized by young doctors and nurses during Covid, promoted the RSV vaccine on social media. Factchequeado, a Spanish language fact-checking initiative, has created a WhatsApp chatbot so people can discern health fact from fiction in their own messages.

And another group is taking a different starting point altogether: listening to local communities themselves. What are they hearing about public health, and what do they need to know? It’s called “iHeard.”

Starting in St. Louis, in conjunction with the public health school at Washington University, iHeard distributes a weekly survey to about 200 people, which can be filled out in about three minutes. It asks about everything from vaccines to contaminated pouches of apple sauce popular with young children. iHeard is now spreading to several other cities across the country.

“We put in place a system, a kind of proactive community listening, to try to get a handle on what people were hearing and when new misinformation might enter the community,” said Washington University public health professor Matthew Kreuter. It began focused on Covid but has pivoted to health more broadly.

The survey information is posted on a public-facing dashboard, and it’s shared with partners in health, education, government and social services. The team also produces messaging that can be used on social media — where people in the community are more likely to see it than on a university dashboard. The whole program has the advantage of involving community voices, which build trust.

The RSV vaccines don’t generate quite as much fury as Covid, for several reasons, including the fact that there are no mandates for this shot, not at jobs, not at schools.

The audience is also narrower: Shots are recommended for people over age 60 and those who are between 32 and 36 weeks pregnant so they can pass on antibodies to the fetus. Infants not protected in utero, and other young children at high risk can get monoclonal antibodies, which isn’t technically a vaccine although it is an injection. Those monoclonal antibodies were in short supply this season, as this was one place where manufacturers apparently underestimated the demand — or overestimated the already considerable hesitancy.

HEALTH CARE

Covid killed 170,000 in nursing homes. Most residents still haven’t gotten the latest shot.

BY CHELSEA CIRRUZZO AND DANIEL PAYNE | JANUARY 26, 2024 03:43 PM

In addition, the target population for RSV shots — people over 60, people having babies — are likely to be connected to the health care system; they’re already patients. That means they are more likely to have a doctor, a nurse or other provider that they know and trust. That’s not the case for some of the more militant anti-vaxxers, who are distrustful of the whole medical establishment. Yet vaccination rates were low.

Finally, public health experts noted, anti-vaccination sentiment is so high right now that the disinformation makers don’t have to go after RSV specifically to instill fear and mistrust in a new shot. It just got wrapped into the whole deepening anti-vaccine gestalt. Routine childhood immunization rates are now down to 93 percent for kindergarteners, below the 95 percent threshold the CDC says is needed to thwart disease outbreaks.

“There’s a level of exhaustion, right?” said Katy Evans, senior program officer at de Beaumont Foundation, one of the groups forming the Public Health Communication Collaborative. “You want me to get three — in some cases, three — vaccines this fall: a Covid booster, a flu shot and an RSV vaccine. And if I am someone who doesn’t really understand why those things are valuable, that feels like a big ask.”

The relatively disappointing uptake on RSV vaccination underscores just how big an ask it was.

Ultimately fighting disinformation comes down to trust. Trust is what a lot of the malevolent messengers are trying to destroy, and trust is what the public health, scientific and clinical worlds have to rebuild. That’s a resource even more valuable than the smarter, faster, better tools being developed to combat misinformation and disinformation.

It can’t just be about “getting ahead of a wacky narrative that resonates” with people who no longer trust doctors or scientists, said ABIM’s Baron. “People are believing this stuff because it is consistent with a narrative they already believe. And we have to get better in constructing a different narrative.”

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #216

Makers of COVID-19 protective equipment seek over $5 billion in damages from Ottawa

OTTAWA — Canadian manufacturers of masks and other equipment for protecting against COVID-19 are seeking more than $5 billion in damages from the federal government, saying Ottawa misled them about buying and helping sell their products.

Makers of COVID-19 protective equipment seek over $5 billion in damages from Ottawa

Canadian Pressabout 2 hours agoabout 2 hours ago

OTTAWA — Canadian manufacturers of masks and other equipment for protecting against COVID-19 are seeking more than $5 billion in damages from the federal government, saying Ottawa misled them about buying and helping sell their products.

In a statement of claim filed in Federal Court, the companies and their industry association allege the government made "negligent misrepresentations" that prompted them to invest in personal protection equipment innovations, manufacturing and production.

The companies and the Canadian Association of PPE Manufacturers say the government made misleading statements about markets, direct assistance, flexible procurement and long-term support over a three-year period that began in March 2020.

The emergence of COVID-19 in early 2020 spurred governments and public-health officials to implement extraordinary measures — including lockdowns, vaccine requirements and mask mandates — to prevent the spread of the disease.

The statement of claim alleges Canada's misrepresentations resulted in about $88 million in investment losses and a further $5.4 billion in projected lost market opportunities over a 10-year period.

The federal government will have an opportunity to file a defence to the unproven allegations as the case proceeds.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #217

COVID patients are 4.3 times more likely to develop chronic fatigue, CDC report finds

A new CDC study published Wednesday found that COVID-19 patients are 4.3 times more likely to develop chronic fatigue than those who have not had the virus.

COVID patients are 4.3 times more likely to develop chronic fatigue, CDC report finds

Women and older people were at higher risk of developing chronic fatigue.ByMary Kekatos

February 14, 2024, 12:29 PM

1:02

COVID-19 patients develop chronic fatigue at higher rate, CDC report finds

COVID-19 patients develop chronic fatigue at higher rate, CDC report finds

A new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also found that women...Show More

COVID-19 patients are at least four times more likely to develop chronic fatigue than someone who has not had the virus, a new federal study published Wednesday suggests.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) looked at electronic health records from the University of Washington of more than 4,500 patients with confirmed COVID-19 between February 2020 and February 2021.

They were followed for a median of 11.4 months and their health data was compared with the data of more than 9,000 non-COVID-19 patients with similar characteristics.

Fatigue developed in 9% of the COVID patients, the team found. Among COVID-19 patients, the rate of new cases of fatigue was 10.2 per 100 person-years and the rate of new cases of chronic fatigue was 1.8 per 100 person-years.

MORE: Long COVID research opens door for further exploration on post-viral illness

Person-years is a type of measurement that multiplies the number of people in a study and the amount of time each person spends in a study. It is useful for evaluating risk.

Compared with non-COVID-19 patients, those who has tested positive were 68% at risk of fatigue and were 4.3 times more likely to develop chronic fatigue in the follow-up period, the study found.

In this undated stock photo, a man is seen resting his head in his hands.

STOCK PHOTO/Getty Images

Fatigue following COVID-19 infection was more common among women, older people and those who had other medical conditions including diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a history of mood disorders.

There was no strong evidence of racial or ethnic differences when it came to developing fatigue after COVID-19 except a slightly lower incidence among Black patients, results also showed.

Additionally, researchers found that patients with COVID-19 who developed fatigue after the infection had far worse outcomes such as hospitalization or death than patients without fatigue.

Among 434 COVID-19 patients in whom fatigue developed, 25.6% were hospitalized more than one time during the follow-up period compared to 13.6% of 4,155 patients without fatigue who were hospitalized.

What's more, COVID-19 patients with fatigue were at higher risk of dying. During the follow-up period, 5.3% with fatigue died compared to 2.3% of those without fatigue.

MORE: About 18 million US adults have had long COVID: CDC

"Our data indicate that COVID-19 is associated with a significant increase in new fatigue diagnoses, and physicians should be aware that fatigue might occur or be newly recognized [more than] one year after acute COVID-19," the authors of the study wrote. "Future study is needed to better understand the possible association between fatigue and clinical outcomes."

The authors added that the high rates of fatigue "reinforce the need for public health actions to prevent infections, to provide clinical care to those in need, and to find effective treatments for post–acute COVID-19 fatigue."

The team said it also hopes that increased awareness of fatigue and other long COVID symptoms helps COVID patients seek early care when needed to reduce their risk.

The results build upon those seen in previous reports including a joint U.S.-U.K. study of electronic health records that found 12.8% of patients received a new fatigue diagnosis within six months of COVID-19 infection.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #218

CDC Tracks New Variant as COVID Winter Wave Recedes

The new version of the virus has only been found in South Africa so far, but is highly mutated.By Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder

|

Feb. 14, 2024, at 2:30 p.m.

Save

More

CDC Tracks Variant as COVID Wave Fades

More

GETTY IMAGES

Several COVID-19 metrics – including hospital admissions and emergency department visits – are showing a decline in the U.S.

The latest COVID-19 wave in the U.S. appears to have peaked and started retreating, but concerns over a new variant are always lurking.

Several COVID-19 metrics – including hospital admissions and emergency department visits – are showing a decline. Wastewater viral activity levels, which represent both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections, remain high but are trending downward in all regions except the South, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data indicates the latest increase in COVID-19 activity was significantly lower – and significantly less dangerous – than the COVID-19 surges the U.S. saw early in the pandemic. New weekly hospital admissions, for example, peaked most recently at nearly 35,000 in early January. That’s compared to an all-time record of more than 150,000 in January 2022.

“The good news of COVID is that the impact of COVID has significantly reduced in recent years, and so we're not seeing as many hospitalizations, as many ICU admissions, as many deaths,” Maria Van Kerkhove, an epidemiologist with the World Health Organization, said during an event earlier this month.

But, she added, COVID-19 still causes a “significant burden.”

“It's hard to articulate and communicate that we're in a better situation, but we're not out of the woods yet,” she said.

Given declines in testing and data reporting, it’s impossible to know how many Americans were infected during the recent uptick. But while COVID-19 is causing severe disease less frequently than it once was, weekly death totals still have routinely topped 1,000 to 2,000 in recent months.

There are also concerns beyond just surviving a coronavirus infection, such as long COVID and the risks posed by reinfection.

“This virus is circulating in every country, and people are getting reinfected multiple times,” Van Kerkhove said. “So we're not only worried about the acute disease and causing death right away, we're worried about post-COVID condition, and we're worried about repeat infection in the long term – so five, 10, 20 years from now on organ function.”

The risks of long COVID and reinfection may see renewed attention in the U.S. as the CDC is reportedly considering dropping its five-day isolation guidance for people who test positive for the coronavirus. Officials told The Washington Post that the White House hasn’t yet approved the guidance change, which is expected to be floated for public feedback in April.

Meanwhile, as is always the case with COVID-19, there’s the possibility a new variant could change everything.

Globally and in the U.S., JN.1 dominates. It’s an omicron subvariant that is closely related to BA.2.86, or “pirola.”

READ:

JN.1 Deepens Hold on the U.S.

JN.1 was responsible for more than 9 in 10 new COVID-19 infections in the U.S. in recent weeks, according to CDC estimates. The agency said JN.1 contributed to the burden of COVID-19 this winter, but added that its spread “does not appear to pose additional risks to public health beyond that of other recent variants.”

As of last week, the CDC was tracking and analyzing a new variant that hadn’t yet appeared in the U.S.: BA.2.87.1. The strain had only been found in South Africa so far.

“The fact that only nine cases have been detected in one country since the first specimen was collected in September suggests it does not appear to be highly transmissible – at least so far,” the CDC said in a post about the strain.

So why is the agency keeping an eye on this variant? Because it has highly mutated, with more than 30 changes in the spike protein of the coronavirus compared with XBB.1.5, which is the virus variant targeted by the latest vaccines.

“In the past year, several variants have had significant changes in their spike protein. Yet despite those changes, existing immunity from vaccines and previous infections still provides good protection,” the CDC said. “We don’t yet know how well existing immunity holds up against BA.2.87.1.

“However, our immune systems now have several years of experience with this virus and vaccines, generally providing protection against a wide range of variants.”

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #219

COVID-19 vaccination and boosting during pregnancy protects infants for six months

Findings reinforce the importance of receiving both a COVID-19 vaccine and booster during pregnancy.

COVID-19 vaccination and boosting during pregnancy protects infants for six months

What

Women who receive an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination or booster during pregnancy can provide their infants with strong protection against symptomatic COVID-19 infection for at least six months after birth, according to a study from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. These findings, published in Pediatrics(link is external), reinforce the importance of receiving both a COVID-19 vaccine and booster during pregnancy to ensure that infants are born with robust protection that lasts until they are old enough to be vaccinated.COVID-19 is especially dangerous for newborns and young infants, and even healthy infants are vulnerable to COVID-19 and are at risk for severe disease. No COVID-19 vaccines currently are available for infants under six months old. Earlier results from the Multisite Observational Maternal and Infant COVID-19 Vaccine (MOMIv-Vax) study revealed that when pregnant volunteers received both doses of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, antibodies induced by the vaccine could be found in their newborns’ cord blood. This suggested that the infants likely had some protection against COVID-19 when they were still too young to receive a vaccine. However, researchers at the NIAID-funded Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Consortium (IDCRC), which conducted the study, did not know how long these antibody levels would last or how well the infants would actually be protected. The research team hoped to gather this information by following the infants through their first six months of life.

In this portion of the study, researchers analyzed data from 475 infants born while their pregnant mothers were enrolled in the MOMI-Vax study. The study took place at nine sites across the United States. It included 271 infants whose mothers had received two doses of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy. The remaining 204 infants in the study were born to mothers who had received both doses of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine as well as a COVID-19 booster. To supplement data gathered during pregnancy and at birth, the infants were evaluated during at least one follow-up visit during their first six months after birth. Parents also reported whether their infants had become infected or had demonstrated COVID-19 symptoms.

Based on blood samples from the infants, the researchers found that newborns with high antibody levels at birth also had greater protection from COVID-19 infection during their first six months. While infants of mothers who received two COVID-19 vaccine doses had a robust antibody response at birth, infants whose mothers had received an additional booster dose during pregnancy had both higher levels of antibodies at birth and greater protection from COVID-19 infection at their follow-up visits.

While older children and adults should continue to follow guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to stay up-to-date on their COVID-19 vaccines and boosters, this study highlights how much maternal vaccination can benefit newborns too young to take advantage of the vaccine: During the course of this study, none of the infants examined required hospitalization for COVID-19. Researchers will continue to evaluate the data from the MOMI-Vax study for further insights concerning COVID-19 protection in infants.

Article

CV Cardemil et al. Maternal COVID-19 Vaccination and Prevention of Symptomatic Infection in Infants. Pediatrics DOI: 10.1542/peds.2023-064252(link is external) (2024).Who

Cristina Cardemil, M.D., a medical officer in NIAID’s Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, is available to comment.Contact

To schedule interviews, please contact Elizabeth Deatrick, (301) 402-1663, [email protected](link sends e-mail).NIAID conducts and supports research—at NIH, throughout the United States, and worldwide—to study the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases, and to develop better means of preventing, diagnosing and treating these illnesses. News releases, fact sheets and other NIAID-related materials are available on the NIAID website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #220

Virus and Booster Apathy Could Be Fueling Long COVID

Debby WaldmanFebruary 14, 2024

11

17

Maria Maio wasn't the only person in her workplace battling COVID-19 in early December 2023. But while everyone else she knows got better, she got long COVID.

A celebrity makeup artist, the 55-year-old New Yorker had been boosted and vaccinated at every opportunity since vaccines were approved at the end of 2020, until the fall of 2023, when she skipped the shot.

"I really started subscribing to the mindset that you have an immune system and your immune system is supposed to work for you," she said. "That was the stupidest thing I've ever done."

Maio was not the only person to skip the latest booster: A recent study reported that while nearly 80% of adults in the United States said they'd received their first series of vaccines, barely 20% were up to date on boosters. Nor was Maio alone in getting long COVID 4 years after the start of the deadliest pandemic in a century.

It's tempting, this far out from the shutdowns of 2020, to think the virus is over, that we're immune, and nobody's going to get sick anymore. But while fewer people are getting COVID, it is still very much a part of our lives. And as Maio and others are learning the hard way, long COVID is, too — and it can be deadly.

For those who have recently contracted long COVID, it can feel as if the whole world has moved on from the pandemic, and they are being left behind.

Too Easy to Let Our Guard Down

"It's really difficult to prevent exposure to COVID no matter how careful you are and no matter how many times you are vaccinated," said Akiko Iwasaki, an immunology professor at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, and pioneer in long COVID research. Iwasaki was quick to point out that "we should never blame anybody for getting long COVID because there is no bulletproof way of preventing long COVID from happening" — although research shows you can increase your protection through vaccination, masking, and increasing ventilation indoors.Also, just because you didn't get long COVID after catching the virus once, doesn't mean you'll dodge the bullet if you get sick again, as Maio has now learned twice. She had long COVID in 2022 after her second bout with the virus, with breathing problems and brain fog that lasted for several months.

Subsequent long COVID experiences won't necessarily mimic previous ones. Although Maio developed brain fog again, this time she didn't have the breathing problems that plagued her in 2022. Instead, she had headaches so excruciating she thought she was dying of a brain aneurysm.

A Journal of the American Medical Association study released in May identified the 37 most common symptoms of long COVID, including symptom subgroups that occurred in 80% of the nearly 10,000 study participants. But the symptoms that patients with long COVID are experiencing now are slightly different from earlier in the pandemic or at least that's what doctors are finding at the Post-COVID Recovery Clinic affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Michael Risbano, MD, the clinic's codirector, said fewer patients have pulmonary or lung damage now than in the past, but a steady stream report problems with brain fog, forgetfulness, exercise intolerance (shortness of breath and fatigue with exercise and difficulty performing any kind of exertional activity), and post-exertional malaise (feeling wiped out or fatigued for hours or even days after physical or mental activity).

Long COVID Treatments Showing Improvement — Slowly

"There still isn't a great way to treat any of this," said Risbano, whose clinic is involved with the National Institute of Health's RECOVER-VITAL trial, which is evaluating potential treatments including Paxlovid and exercise to treat autonomic dysfunction with similarities to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and POTS, exercise intolerance, and neurocognitive effects such as brain fog.Risbano and colleagues have found that physical therapy and exercise training have helped patients with exercise intolerance and neurocognitive problems. "It's not a quick thing where they go through one visit and are better the next day," he stressed. "It takes a little bit of time, a little bit of effort, a little bit of homework — there are no silver bullets, no magic medications."

A quick fix was definitely not in the cards for Dean Jones, PhD, who could barely move when he developed long COVID in May 2023. A 74-year-old biochemist and professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, he'd recovered fully the first time he had COVID, in August 2022, but had a completely different experience the second time. He had been vaccinated four times when he began experiencing chronic fatigue, intense exertion-induced migraines, severe airway congestion, brain fog, and shortness of breath. The symptoms began after Memorial Day and worsened over the next month.

His resting heart rate began racing even when he was sleeping, jumping from 53 to 70 beats per minute. "It was almost as though the virus had hit my heart rather than the lungs alone," he said.

Doctors prescribed multiple inhalers and glucocorticoids to calm Jones's immune system. The worst symptoms began to abate after a few weeks. The bad ones continued for fully 2 months, severely limiting Jones's activity. Although he no longer slept all day, just walking from one room to another was exhausting. A dedicated scientist who typically worked 10-15 hours a day before getting sick, he was lucky to focus on work-related tasks for a fraction of that time.

Although the migraines went away early on, the headaches remained until well into the fall. Jones's energy level gradually returned, and by Christmas, he was beginning to feel as healthy as he had before getting COVID in May.

Still, he's not complaining that it took so long to get better. "At 74, there's a lot of colleagues who have already passed away," he said. "I respect the realities of my age. There are so many people who died from COVID that I'm thankful I had those vaccines. I'm thankful that I pulled through it and was able to rebound."

Time Helps Healing — But Prompt Care Still Needed

Recovery is the case for most patients with long COVID, said Lisa Sanders, MD, medical director of the Yale New Haven Health Systems Long COVID Consultation Clinic, which opened in March 2023. Although the clinic has a small segment of patients who have had the condition since 2020, "people who recover, who are most people, move on," she said. "Even the patients who sometimes have to wait a month or so to see me, some of them say, 'I'm already starting to get better. I wasn't sure I should come.'"Maio, too, is recovering but only after multiple visits to the emergency room and a neurologist in late December and early January. The third emergency room trip was prompted after a brief episode in which she lost the feeling in her legs, which began convulsing. A CAT scan showed severely constricted blood vessels in her brain, leading the medical team to speculate she might have reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), which can trigger the thunderclap headaches that had been causing her such misery.

After her third such headache prompted a fourth emergency room visit, further tests confirmed RCVS, which doctors said was related to inflammation caused by COVID. Maio was then admitted to the hospital, where she spent 4 days starting on a regimen of blood pressure medication, magnesium for the headaches, and oxycodone for pain management.

The TV show Maio works on went back into production after the holidays. She went back at the end of January. She's still having headaches, though they're less intense, and she's still taking medication. She was scheduled for another test to look at her blood vessels in February.

Maio has yet to forgive herself for skipping the last booster, even though there's no guarantee it would have prevented her from getting sick. Her message for others: it's better to be safe than to be as sorry as she is.

"I'll never, ever be persuaded by people who don't believe in vaccines because I believe in science, and I believe in vaccines — that's why people don't die at the age of 30 anymore," she said. "I really think that people need to know about this and what to expect. Because it is horrendous. It is very painful. I would never want anyone to go through this. Ever."

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #221

The CDC is finally going to loosen Covid isolation guidelines. Here’s why that’s a good thing.

Isolation policies haven’t stopped Covid’s worst outcomes. Other, better policies might.

www.vox.com

www.vox.com

The CDC is finally going to loosen Covid isolation guidelines. Here’s why that’s a good thing.

Isolation policies haven’t stopped Covid’s worst outcomes. Other, better policies might.By Keren Landman, MD@landmanspeaking Feb 14, 2024, 6:05pm EST

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook (opens in new window)

- Share this on Twitter (opens in new window)

- SHAREAll sharing options

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73140461/GettyImages_1284429703.0.jpg)

Keren Landman, MD is a senior reporter covering public health, emerging infectious diseases, the health workforce, and health justice at Vox. Keren is trained as a physician, researcher, and epidemiologist and has served as a disease detective at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On February 13, the Washington Post reported that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) plans to issue new guidelines that would substantially pull back on recommendations for people infected with Covid-19.

The guidelines, which are expected to drop in April, will reportedly no longer recommend that most Americans infected with the virus stay away from work and school for five days. Instead, they will advise people that they can leave home if they’ve been fever-free for at least 24 hours (without fever-reducing medicine like ibuprofen or acetaminophen) and have mild and improving symptoms. The Post’s story didn’t mention whether or how the new guidelines would recommend using tests to guide decision-making.

“It’s a reasonable move,” says Aaron Glatt, an infectious disease doctor and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau Hospital on Long Island. “When you’re doing public health, you have to look at what is going to be listened to, and what is doable.”

Guidelines that adhere to the highest standards of infection control might please purists in public health who don’t have to make policies for the real world. However, guidelines that seem to acknowledge that workers often don’t have paid sick leave and emergency child care, and that social interactions are important to folks, are more likely not only to be followed but to engender trust in public health authorities.

This change likely won’t increase exposure risk for the people most vulnerable to severe Covid-19

It’s important to note that the new recommendations will be aimed toward the broader community and the people who live, work, and go to school in it — not toward hospitals, nursing homes, and other facilities whose residents are both less socially mobile and more vulnerable to the virus’s worst effects.That means the people who are at higher risk of getting severely ill or dying if they get infected — people who are older and sicker at baseline — will likely be subject to different, more conservative guidelines. Which makes sense, says Glatt: “It’s not the same approach in a 4-year-old kid as it is in a nursing home. It shouldn’t be.”

Covid-19 hospitalization rates among adults 65 and over are at least four times what they are in other age groups, and rates are particularly high among adults 75 and over, according to the CDC. In a study published in October, the agency reported that those 65 and older constituted nearly 90 percent of Covid-19 deaths in hospitals.

The older adults getting hospitalized and dying with Covid-19 now are not the otherwise well people with active work and social lives who were getting severely ill earlier in the pandemic, says Shira Doron, an infectious disease doctor and hospital epidemiologist at Tufts Medicine in Boston. They’re people with severe underlying illness and compromised immune systems — and for many, it’s not even clear Covid-19 is what’s causing their decline. “I’m really struck by how totally different the Covid inpatient population — even the Covid death population that I’m seeing — is from 2020, or even 2021,” she says.

It’s hard to tell exactly how many of the worst-affected adults are infected in facilities like hospitals and nursing homes — in other words, how many of them would be relatively unaffected by a revised set of guidelines. It’s also hard to tell how many older adults, aware of their higher risk, take more measures to protect themselves in public, like wearing masks and gathering outdoors.

However, it’s worth noting the experiences of states that have already loosened recommendations. Since Oregon loosened its guidelines in May 2023, the state has not seen unusual increases in transmission or severity; California made similar changes in January 2024. In revising their recommendations, state officials hoped to reduce the burdens on workers without sick leave and reduce disruptions on schools and workplaces, according to the Post’s reporting.

Doron says the reason loosened isolation guidelines haven’t led to mayhem in Oregon — nor in Europe, where the recommendations changed two years ago — is because isolation never did much to reduce transmission to begin with. “This has nothing to do with the science of contagiousness and the duration of contagiousness. It has to do with [the fact that] it wasn’t working anyway,” she says.

Leaning away from what doesn’t work to reduce the virus’s impact — and toward what does work — is a smarter way forward, she says.

Revising testing guidelines would free up resources for interventions that actually work

Isolation guidelines haven’t been effective for mitigating Covid-19 harms because so many people simply do what they want, regardless of whether they’re sick — and they may avoid reporting symptoms to avoid being forced to comply with an isolation policy.Imagine a workplace or school policy adheres to the current CDC guidelines, which recommend that people who test positive for Covid-19 infection stay home for at least five days. That policy creates a “perverse incentive” for some people who have symptoms to avoid getting tested, Doron says, because they don’t want to miss school, work, or a social event. Because so many people don’t have paid sick time, acknowledging even mild symptoms can lead to real financial losses when it means missing a week of work.

At the same time, because these guidelines build testing into their protocols, they lead lots of other people — and the federal government — to spend money on at-home tests, which are often inaccurate early in infection. That’s a waste of resources that could save more lives if they were instead spent on providing tests to people likeliest to benefit from Paxlovid and getting them treated, says Doron.

For that reason, she thinks that in addition to changing isolation guidelines, the CDC should change the guidelines around testing. “You should only be testing when it will change something, and that should be because you need Paxlovid or an antiviral,” Doron says. (Clarity and greater focus on who qualifies for Paxlovid would also be helpful, she says — current CDC recommendations are too broad.)

In the long term, CDC guidelines should normalize being considerate

The CDC’s revised guidelines likely won’t be formally released until April at the earliest, and their details are as yet unclear. While they’re recommendations, not requirements, employers and state and local health departments often use them to guide their own policies.One area where a new set of guidelines could make a big difference is in elevating and normalizing masking, says Jay Varma, an epidemiologist and biotechnology executive with extensive experience in state and federal public health practice. He hopes the new recommendations lean heavily into putting forth masking in public as a matter of routine for people who leave home as soon as they feel well.

“CDC should be thinking of this as a decades-long effort to promote cultural acceptance that being in public with a mask is similar to washing your hands, wearing a condom, or smoking outdoors: It’s a form of politeness and consideration for others,” Varma wrote in an email to Vox.

After all, in the long term, it’s a lot easier to change social norms around masking than it is to get people used to giving up their social lives for days or weeks at a time.

It would also be helpful for public health officials to encourage people to factor in who gets exposed if they leave isolation soon after a Covid diagnosis, says Glatt. It’s hard to build nuance into a one-size-fits-all recommendation, but the guidelines could suggest that, for example, people who have regular social contact with someone they know takes high-dose immunosuppressive medications act differently than people who don’t have that kind of contact.

“That’s something that’s very difficult for a guideline to take into account,” he acknowledges.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #224

Confirmed COVID-19 infection numbers show slow decline

COVID rates show little change

COVID-19 infection numbers show slow decline

Author of the article:Staff Reporter

Published Feb 15, 2024 • 1 minute read

Join the conversation

Article content

COVID-19 infections showed a slight drop in recent days, but experts say people should remain cautious.Ottawa Public Health’s reported 130 new cases and two new deaths during the period ending Feb. 13.

Article content

Last week, there were 144 new cases and four additional deaths.

Tuesday’s reading brought the total number of cases to 98,089, while 1,224 people have died.

OPH’s weekly respiratory and enteric surveillance dashboard showed five new hospitalizations for flu patients, for a total of 173 this season. The report described the level as “high, but decreasing since last week.”

There were 47 hospitalizations for COVID-19 patients, described as “high and increasing since last week.” Seven patients were hospitalized for other respiratory infections, described as “high and similar to last week.”

Percent positivity levels were 11.7 per cent for flu, 13.3 per cent for COVID-19 and 1.7 for other respiratory conditions. The report described these levels as moderate and similar to last week for flu and COVID, and low and similar to last week for the

Wastewater surveillance levels for flu and COVID-19 remained fairly high and rising, OPH reported. Levels for other respiratory issues were moderate and declining.

There were five new outbreaks of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, for a total of 10 ongoing outbreaks. There was one new flu outbreak, for a total five ongoing, while there was one new outbreak of other respiratory condition.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,188

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #225

Quintana's European return delayed by Covid

Former Giro and Vuelta winner Nairo Quintana has been ruled out of next week's Gran Camino race after contracting a bout of Covid, the Colombian announced on Thursday.

Quintana's European return delayed by Covid

Madrid (AFP) – Former Giro and Vuelta winner Nairo Quintana has been ruled out of next week's Gran Camino race after contracting a bout of Covid, the Colombian announced on Thursday.Issued on: 15/02/2024 - 13:03Modified: 15/02/2024 - 13:00

1 min

ADVERTISING

Quintana made his return to cycling with Movistar after a doping ban in the Tour Colombia earlier this month, finishing 21st in the 6-stage event.

"I finished the Tour Colombia very sick. I already felt quite bad from the previous days," the diminutive 34-year-old climb specialist said.

Quintana was one of the main attractions for the Gran Camino alongside defending champion and two-time Tour de France winner Jonas Vingegaard (Visma-Lease a Bike) and Olympic champion Richard Carapaz (Education First).

The four-day race begins in the port of La Coruna on February 22 and runs through the rugged Galician hills and Atlantic coastline before finishing in Tui.

Quintana came close to retiring in 2022 when he tested positive for tramadol but made a spectacular return to Spanish team Movistar in October, with whom he won the 2014 Giro and the 2016 Vuelta.

Quintana raced seven seasons with Movistar until 2019, and his return at the head of the team is much anticipated.

"It’s super emotional for me to be back home," said the 1.67-metre climber in January.

"It’s been such a tough year. The sleepless nights, so many days of sacrifice.

"But it was all worth it. I won’t waste this opportunity. I know the values of the team, the values of sport.

"I will give my everything to do things right and I want to help the team achieve the best results."

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)

Pakistan Defence Latest

-

-

A GIDS Shahpar II UAV of the PAF broke midair and crashed near Darya Khan, Punjab (3 Viewers)

- Latest: Broghil

-

-

-

Country Watch Latest

-

Pakistan to Deliver First Batch of Anti-Tank Guided Missiles to Bangladesh (5 Viewers)

- Latest: hasn2009

-

Why India Deliberately kept Weakened Bangladesh’s Military | InShort (10 Viewers)

- Latest: Vikramaditya1

-

Strategic Defense Options for Small Economies: How Can Bangladesh Effectively Defend Itself? (2 Viewers)

- Latest: Vikramaditya1

-

-

Latest Posts

-

Pakistan to Deliver First Batch of Anti-Tank Guided Missiles to Bangladesh (5 Viewers)

- Latest: hasn2009

-

Why India Deliberately kept Weakened Bangladesh’s Military | InShort (10 Viewers)

- Latest: Vikramaditya1

-

Strategic Defense Options for Small Economies: How Can Bangladesh Effectively Defend Itself? (2 Viewers)

- Latest: Vikramaditya1

-

-