Yommie

Elite Member

- Oct 2, 2013

- 56,039

- 36,740

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #1,201

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/LB.1COVIDvariant-9865c8f38bb4460393c16aea1c45e10a.png)

New COVID Subvariant LB.1 on the Rise in U.S., Experts Say Vaccination Is Still Key

A new COVID-19 subvariant may fuel more summer cases in the U.S.

What to Know About the LB.1 COVID-19 Variant

By John LoeppkyPublished on July 02, 2024

Fact checked by Nick Blackmer

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/LB.1COVIDvariant-9865c8f38bb4460393c16aea1c45e10a.png)

Photo Illustration by Michela Buttignol for Verywell Health; Getty Images

Key Takeaways

- LB.1 is the latest COVID-19 subvariant to emerge in the U.S.

- Current rapid tests and treatments like Paxlovid are still effective, and updated vaccines in the fall should offer sufficient protection.

Bernadette Boden-Albala, DrPH, MPH, director of the public health program at UC Irvine, said that the public should expect similar symptoms from LB.1, an Omicron offshoot, as its predecessors.

“There is no evidence today that the LB.1 variant is causing different or more severe symptoms compared to past variants. The real difference is on an individual’s immunity either built up by maintaining adherence with booster vaccines or a combination of past COVID-19 infections,” Boden-Albala told Verywell.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said LB.1 is likely to play a part in the summer surge of COVID.

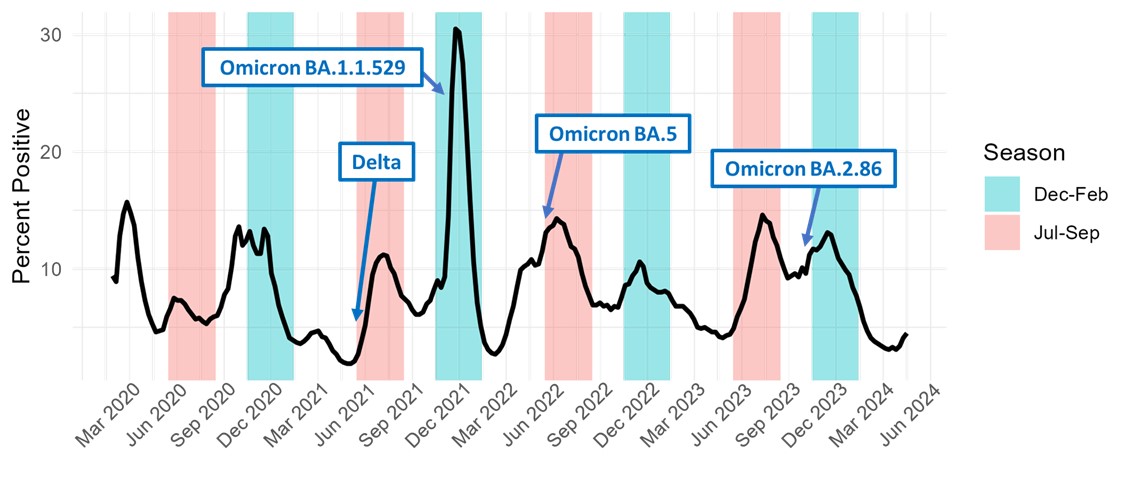

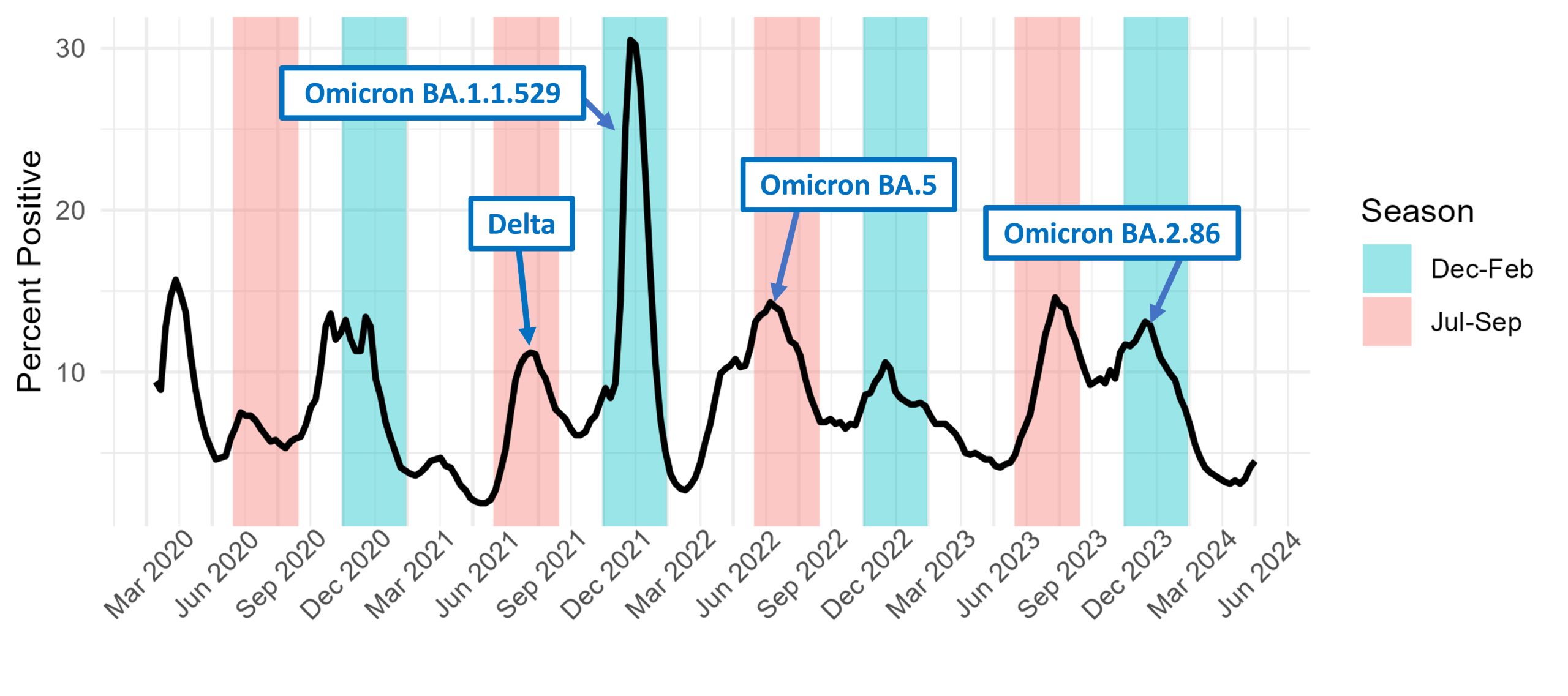

“Now that we have LB.1 out there and KP.3 still circulating, they are fueling the summer increase that we’re starting to see in many states,” Schaffner told Verywell. “It abates in the fall, and then we have a more substantial increase in the winter.”

A preprint study in Japan suggests that LB.1 may be more infectious and better at evading immunity than KP.2 due to a mutation called S:S31del.1

Because of the rapidly changing variant landscape, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) asked vaccine manufacturers to target KP.2 instead of JN.1 for the fall COVID vaccine update, if possible. Health experts say that the updated vaccine will offer enough protection against LB.1 even if it doesn’t target this variant specifically.

Schaffner said Paxlovid, the antiviral medication for COVID, will still work against new variants. However, older adults, pregnant people, and those people who have underlying conditions are still at the highest risk of severe illness from COVID.

Boden-Albala added that wastewater surveillance is helpful in providing “an early warning” to communities that may be seeing spikes in cases, although the data could sometimes change in less than a week. Vaccination and ongoing public health measures will manage the impact of COVID, she said, but “surges will remain commonplace.”

“Continuous vigilance, vaccination updates, and adaptive health strategies will be essential in coexisting with the virus,” Boden-Albala said.