Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Covid-19 News and Discussions

- Thread starter Yommie

- Start date

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,187

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #2,035

Discovery of how blood clots harm brain and body in COVID-19 points to new therapy

In a study that reshapes what we know about COVID-19 and its most perplexing symptoms, scientists have discovered that the blood coagulation protein fibrin causes the unusual clotting and inflammation that have become hallmarks of the disease, while also suppressing the body's ability to clear...

August 28, 2024

Editors' notes

Discovery of how blood clots harm brain and body in COVID-19 points to new therapy

by Gladstone Institutes

In a study that reshapes what we know about COVID-19 and its most perplexing symptoms, scientists have discovered that the blood coagulation protein fibrin causes the unusual clotting and inflammation that have become hallmarks of the disease, while also suppressing the body's ability to clear the virus.

Importantly, the team also identified a new antibody therapy to combat all of these deleterious effects.

Published in Nature, the study by Gladstone Institutes and collaborators overturns the prevailing theory that blood clotting is merely a consequence of inflammation in COVID-19.

Through experiments in the lab and with mice, the researchers show that blood clotting is instead a primary effect, driving other problems—including toxic inflammation, impaired viral clearance, and neurological symptoms prevalent in those with COVID-19 and long COVID.

The trigger is fibrin, a protein in the blood that normally enables healthy blood coagulation, but has previously been shown to have toxic inflammatory effects. In the new study, scientists found that fibrin becomes even more toxic in COVID-19 as it binds to both the virus and immune cells, creating unusual clots that lead to inflammation, fibrosis, and loss of neurons.

"Knowing that fibrin is the instigator of inflammation and neurological symptoms, we can build a new path forward for treating the disease at the root," says Katerina Akassoglou, Ph.D., a senior investigator at Gladstone and the director of the Center for Neurovascular Brain Immunology at Gladstone and UC San Francisco.

"In our experiments in mice, neutralizing blood toxicity with fibrin antibody therapy can protect the brain and body after COVID infection."

From the earliest months of the pandemic, irregular blood clotting and stroke emerged as puzzling effects of COVID-19, even among patients who were otherwise asymptomatic.

Later, as long COVID became a major public health issue, the stakes grew even higher to understand the cause of this disease's other symptoms, including its neurological effects. More than 400 million people worldwide have had long COVID since the start of the pandemic, with an estimated economic cost of about $1 trillion each year.

Flipping the conversation

Many scientists and medical professionals have hypothesized that inflammation from the immune system's rapid reaction to the COVID-causing virus is what leads to blood clotting and stroke. But even at the dawn of the pandemic in 2020, that explanation didn't sound right to Akassoglou and her scientific collaborators."We know of many other viruses that unleash a similar cytokine storm in response to infection, but without causing blood clotting activity like we see with COVID," says Warner Greene, MD, Ph.D., senior investigator and director emeritus at Gladstone, who co-led the study with Akassoglou.

"We began to wonder if blood clots played a principal role in COVID—if this virus evolved in a way to hijack clotting for its own benefit," Akassoglou adds.

Indeed, through multiple experiments in mice, the researchers found that the virus spike protein directly binds to fibrin, causing structurally abnormal blood clots with enhanced inflammatory activity. The team leveraged genetic tools to create a specific mutation that blocks only the inflammatory properties of fibrin without affecting the protein's beneficial blood-clotting abilities.

When mice were genetically altered to carry the mutant fibrin or had no fibrin in their bloodstream, the scientists found that inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and clotting in the lungs didn't occur or were much reduced after COVID-19 infection.

In addition to discovering that fibrin sets off inflammation, the team made another important discovery: fibrin also suppresses the body's "natural killer," or NK, cells, which normally work to clear the virus from the body. Remarkably, when the scientists depleted fibrin in the mice, NK cells were able to clear the virus.

These findings support the view that fibrin is necessary for the virus to harm the body.

Mechanism not triggered by vaccines

The fibrin mechanism described in the paper is not related to the extremely rare thrombotic complication with low platelets that has been linked to adenoviral DNA COVID-19 vaccines, which are no longer available in the U.S.By contrast, in a study of 99 million COVID-vaccinated individuals led by The Global COVID Vaccine Safety Project, vaccines that leverage mRNA technology to produce spike proteins in the body exhibited no excessive clotting or blood-based disorders that met the threshold for safety concerns. Instead, mRNA vaccines protect from clotting complications otherwise induced by infection.

Protecting the brain

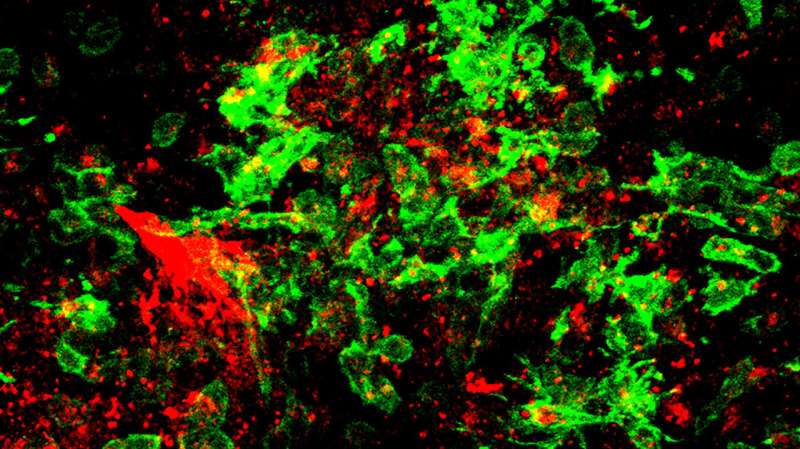

Akassoglou's lab has long investigated how fibrin that leaks into the brain triggers neurologic diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease and multiple sclerosis, essentially by hijacking the brain's immune system and setting off a cascade of harmful, often irreversible, effects.The team now showed that in COVID-infected mice, fibrin is responsible for the harmful activation of microglia, the brain's immune cells involved in neurodegeneration. After infection, the scientists found fibrin together with toxic microglia and when they inhibited fibrin, the activation of these toxic cells in the brains of mice was significantly reduced.

"Fibrin that leaks into the brain may be the culprit for COVID-19 and long COVID patients with neurologic symptoms, including brain fog and difficulty concentrating," Akassoglou says. "Inhibiting fibrin protects neurons from harmful inflammation after COVID-19 infection."

The team tested its approach on different strains of the virus that causes COVID-19, including those that can infect the brain and those that do not. Neutralizing fibrin was beneficial in both types of infection, pointing to the harmful role of fibrin in the brain and body in COVID-19 and highlighting the broad implications of this study.

A new potential therapy

This study demonstrates that fibrin is damaging in at least two ways: by activating a chronic form of inflammation and by suppressing a beneficial NK cell response capable of clearing virally infected cells."We realized if we could neutralize both of these negative effects, we could potentially resolve the severe symptoms we're seeing in patients with COVID-19 and possibly long COVID," Greene says.

Akassoglou's lab previously developed a drug, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody, that acts only on fibrin's inflammatory properties without adverse effects on blood coagulation and protects mice from multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease.

In the new study, the team showed that the antibody blocked the interaction of fibrin with immune cells and the virus. By administering the immunotherapy to infected mice, the team was able to prevent and treat severe inflammation, reduce fibrosis and viral proteins in the lungs, and improve survival rates.

In the brain, the fibrin antibody therapy reduced harmful inflammation and increased survival of neurons in mice after infection.

A humanized version of Akassoglou's first-in-class fibrin-targeting immunotherapy is already in Phase I safety and tolerability clinical trials in healthy people by Therini Bio. The drug cannot be used on patients until it completes this Phase I safety evaluation, and then would need to be tested in more advanced trials for COVID-19 and long COVID.

Looking ahead to such trials, Akassoglou says patients could be selected based on levels of fibrin products in their blood—a measure believed to be a predictive biomarker of cognitive impairment in long COVID.

"The fibrin immunotherapy can be tested as part of a multipronged approach, along with prevention and vaccination, to reduce adverse health outcomes from long COVID," Greene adds.

The power of team science

The study's findings intersect the scientific areas of immunology, hematology, virology, neuroscience, and drug discovery—and required many labs across institutions to work together to execute experiments required to solve the blood-clotting mystery.Akassoglou founded the Center for Neurovascular Brain Immunology at Gladstone and UCSF in 2021 specifically for the purpose of conducting multidisciplinary, collaborative studies that address complex problems.

"I don't think any single lab could have accomplished this on their own," says Melanie Ott, MD, Ph.D., director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology and co-author of the study, noting important contributions from teams at Stanford, UC San Francisco, UC San Diego, and UCLA. "This tour-de-force study highlights the importance of collaboration in tackling these big questions."

Not only did this study address a big question, but it did so in a way that paves a clear clinical path for helping patients who have few options today, says Lennart Mucke, MD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease.

"Neurological symptoms of COVID-19 and long COVID can touch every part of a person's life, affecting cognitive function, memory, and even emotional health," Mucke says. "This study presents a novel strategy for treating these devastating effects and addressing the long-term disease burden of the SARS-CoV-2 virus."

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,187

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #2,036

Woman diagnosed with long COVID discusses feeling ‘isolated and not understood’ - New Brunswick | Globalnews.ca

In January 2022, Anne Belliveau-Leblanc of New Brunswick was diagnosed with long COVID after a COVID-19 infection. She says dealing with the diagnosis was isolating and scary.

Woman diagnosed with long COVID discusses feeling ‘isolated and not understood’

By Suzanne Lapointe Global News

Posted August 28, 2024 5:00 am

Updated August 27, 2024 5:30 pm

2 min read

Video will begin after these messages...

close video

WATCH: A New Brunswick woman is publishing a book about her experiences with long COVID. She says she hopes it will help others going through the same health-care problems feel less alone. Suzanne Lapointe reports.

Leave a commentShare this item on FacebookShare this item on TwitterSend this page to someone via emailSee more sharing options

Descrease article font size

Increase article font size

A New Brunswick woman who was diagnosed with long COVID hopes penning a book about her experiences will help others struggling with the condition.

Anne Belliveau-LeBlanc comes to her summer home in Bouctouche, N.B., to be near the water, to relax and to meditate. For the author, the break is essential to maintaining her health.

In January 2022, she was diagnosed with long COVID after a COVID-19 infection.

“I had a hard time with my brain. Like the brain fog and, the memory, just feeling tired,” she said.

“The feeling that my body wasn’t right. I couldn’t go up three steps. I was so short of breath, I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t talk. My breathing was too short.”

While she had the support of her husband and her family, she says dealing with the relatively new diagnosis was isolating and scary. She wrote down her thoughts in a journal to help her navigate through it.

Story continues below advertisement

1:45Fallout ensues after the closure of long-COVID outpatient program

Those words are now being turned into a book.

Get weekly health news

Receive the latest medical news and health information delivered to you every Sunday.Sign up for weekly health newsletterSign Up

By providing your email address, you have read and agree to Global News' Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy.

“I know that they feel isolated and not understood and a lot of time they suffer by themselves. So I thought maybe my book will help them see that there’s hope.”

According to a Statistics Canada survey released in December 2023, 19 per cent of Canadian adults infected with COVID-19 reported experiencing long-term symptoms.

That’s why Belliveau-LeBlanc says it’s vital for resources to be available for patients.

She adds that while her family doctor tried to help her, there is a lack of specialized long COVID care available in New Brunswick. She believes the province should consider creating clinics focused on long COVID.

“I feel that everybody that has long COVID in New Brunswick are left alone, and they’re by themselves, and they have to find their own way,” she said.

Story continues below advertisement

A spokesperson for the province’s Department of Health told Global News that those with long COVID should contact their health-care provider for the next steps.

Meanwhile, Belliveau-LeBlanc’s book is being published in French next month. She may look into having it translated into English if there is enough interest.

“If it can help one person, I’ll be happy. And it was worth making the book.”

— with a file from Global News’ Rebecca Lau

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,173

- 37,187

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #2,038

Ontario Ends COVID-19 Wastewater Surveillance: What Next?

The program's end will leave the Canadian province without a valuable tool for monitoring infectious disease.

Ontario Ends COVID-19 Wastewater Surveillance: What Next?

Gwendolyn RakAugust 28, 2024

0

2

The Ontario government ended its COVID-19 wastewater surveillance program in late July amid a surge in cases.

The program began in the fall of 2020, when the provincial government offered to support several academic laboratories' wastewater surveillance efforts. It provided funding to the researchers and grew to include 13 labs that sampled hundreds of sites across Ontario. That funding, however, was abruptly cut off on July 31.

Although Ontario's program is ending, the federal government will continue its wastewater surveillance across Canada, which includes one site in Toronto. In a statement provided to Medscape Medical News, the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks said that the federal government is working with Ontario to expand its wastewater sampling to additional sites in the province while Ontario winds down its Wastewater Surveillance Initiative. "The Ministry of Health and the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks will work with the federal government and propose sampling sites that provide quality data for public health across the province," the statement continued.

Researchers, including Robert Delatolla, PhD, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, who helped lead the Ontario wastewater surveillance program, are waiting for the Public Health Agency of Canada to announce which sites in the province they will monitor. Delatolla's research group was among the first to detect COVID-19 in wastewater in April 2020.

Reducing the number of testing locations would have been understandable, he said. Keeping a portion of the program "would have allowed them to benefit from all the knowledge that they gained over the last 3.5 years — and their $80 million investment."

Pandemic Preparedness

Wastewater testing is an effective and efficient tool for monitoring infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza. While the method existed before 2020, the pandemic encouraged researchers like Delatolla to develop it further, and it quickly showed potential as an early detection system for surges in infections, according to Marc-André Langlois, PhD, a molecular virologist and professor at the University of Ottawa who serves as director of the CoVaRR-Net research network. Wastewater research is among the main initiatives of CoVaRR-Net, which studies emerging COVID variants.The government of Canada was among the "late adopters" of wastewater monitoring, Langlois added. "Their program was slow to deploy, and the researchers really had a head start in developing new technologies." Now, the method has been demonstrated as a reliable and cost-effective leading indicator; surges in wastewater occur about a week before hospitalizations, and the data allow hospitals to prepare by increasing staffing. New sequencing techniques can also detect pathogens that aren't otherwise known to be spreading.

The end of Ontario's wastewater surveillance program is "a huge blow" to the ability to track the uptick of new pathogens, said Langlois. "By cutting funding to these programs, we're basically losing access to near real-time data."

The decision is particularly concerning now, Langlois said, with the emergence of infectious diseases like avian flu, a virus with "pandemic potential," and mpox, which the World Health Organization recently declared a public health emergency. Wastewater monitoring is "an extremely valuable tool in the pandemic preparedness arsenal," he said. Langlois believes that ending Ontario's program is counterproductive and the wrong decision.

Healthcare Planning

Compared with the methods and objectives of federal monitoring, those of the provincial program were quite different, Delatolla said. National programs serve as a tool for general pandemic preparedness. But regional monitoring provides data that are local, sampled frequently, and reported quickly, making it doubly useful for healthcare planning at hospitals and public health units.The Ontario program also involved close collaboration with public health officials. "When you have these close relationships within the region, between the people taking the data and the institutions using the data, they seem to be more actionable," said Delatolla. But when data are reported less frequently, "you lose the ability for those institutions to really respond."

The collaboration between researchers and public health officials was a key component of Ontario's program, according to Mark Servos, PhD, a research scientist and Canada research chair in water quality protection at the University of Waterloo in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. Originally a fisheries biologist, Servos was among the first researchers to help develop COVID wastewater testing as part of the initial "grassroots" efforts.

For most of the program, Servos and his colleagues reported the data to an advisory committee two or three times per week — even daily at one point. He also met with public health units weekly to review the data, looking at trends and comparing wastewater with clinical testing data. Together, they would discuss how to interpret the data on public dashboards. "It was a very rapid turnaround in a close, collaborative relationship with the public health units," Servos said. The federal program is "more like just generating information."

Legacy of Knowledge

The end of Ontario's program was disappointing to Servos. Although he understands to some extent, the decision was shortsighted, he added. Wastewater testing provides an important, large dataset that is independent of other clinical measures. "We always joke that it's an extra leg on the stool," Servos said.In addition to losing those data and the relationship between research labs and public health officials, "now we've dismantled the lab," Servos said. Without funding, researchers will move to other projects, so it would be difficult to bring back those qualified to conduct the surveillance. "Our ability to respond quickly to a change would be very limited."

While a very large-scale program may not be necessary, Servos believes there should be an ongoing, core program that is designed strategically and can expand when needed. Enacting such a program would better maintain the "huge legacy of knowledge and capability that was generated," Servos said. Research is also needed to continue learning and adapting for the next threat. It's important not to forget the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and remain prepared for future pandemics, he added.

"The wastewater surveillance program in Ontario was a massive success," Servos emphasized. "It was a success because of the open collaboration among the scientists, the public health units, and the municipalities."

Gwendolyn Rak is a health reporter for Medscape Medical News based in Philadelphia.

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)

Pakistan Defence Latest

-

Indian general praises professionalism of Pakistani peacekeepers in South Sudan (7 Viewers)

- Latest: onlinpunit

-

-

-

Country Watch Latest

-

Why India Deliberately kept Weakened Bangladesh’s Military | InShort (8 Viewers)

- Latest: Hakikat ve Hikmet

-

-

Iran Cyber Security and Artificial Intelligence (civilian and military) (4 Viewers)

- Latest: Immortals

-

-

Latest Posts

-

Why India Deliberately kept Weakened Bangladesh’s Military | InShort (8 Viewers)

- Latest: Hakikat ve Hikmet

-

-

-

-