Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Covid-19 News and Discussions

- Thread starter Yommie

- Start date

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,183

- 37,190

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #1,331

Long COVID puzzle pieces are falling into place – the picture is unsettling

A new study finds the risks of developing long COVID declined over the first two years of the pandemic. But unvaccinated adults were more than twice as likely to get long COVID compared with those who were vaccinated.

theconversation.com

theconversation.com

Long COVID puzzle pieces are falling into place – the picture is unsettling

Published: July 18, 2024 7.02pm EDTAuthor

Ziyad Al-Aly

Ziyad Al-Aly

Chief of Research and Development, VA St. Louis Health Care System. Clinical Epidemiologist, Washington University in St. Louis

Disclosure statement

Ziyad Al-Aly receives funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.Partners

View all partners

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

Republish this articleX (Twitter)

Facebook808

Since 2020, the condition known as long COVID-19 has become a widespread disability affecting the health and quality of life of millions of people across the globe and costing economies billions of dollars in reduced productivity of employees and an overall drop in the work force.

The intense scientific effort that long COVID sparked has resulted in more than 24,000 scientific publications, making it the most researched health condition in any four years of recorded human history.

Long COVID is a term that describes the constellation of long-term health effects caused by infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. These range from persistent respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath, to debilitating fatigue or brain fog that limits people’s ability to work, and conditions such as heart failure and diabetes, which are known to last a lifetime.

I am a physician scientist, and I have been deeply immersed in studying long COVID since the early days of the pandemic. I have testified before the U.S. Senate as an expert witness on long COVID, have published extensively on it and was named as one of Time’s 100 most influential people in health in 2024 for my research in this area.

Over the first half of 2024, a flurry of reports and scientific papers on long COVID added clarity to this complex condition. These include, in particular, insights into how COVID-19 can still wreak havoc in many organs years after the initial viral infection, as well as emerging evidence on viral persistence and immune dysfunction that last for months or years after initial infection.

Early on in the pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 virus seemed to be primarily wreaking havoc on the lungs. But researchers quickly realized that it was affecting many organs in the body. Uma Shankar sharma/Moment via Getty Images

How long COVID affects the body

A new study that my colleagues and I published in the New England Journal of Medicine on July 17, 2024, shows that the risk of long COVID declined over the course of the pandemic. In 2020, when the ancestral strain of SARS-CoV-2 was dominant and vaccines were not available, about 10.4% of adults who got COVID-19 developed long COVID. By early 2022, when the omicron family of variants predominated, that rate declined to 7.7% among unvaccinated adults and 3.5% of vaccinated adults. In other words, unvaccinated people were more than twice as likely to develop long COVID.While researchers like me do not yet have concrete numbers for the current rate in mid-2024 due to the time it takes for long COVID cases to be reflected in the data, the flow of new patients into long COVID clinics has been on par with 2022.

We found that the decline was the result of two key drivers: availability of vaccines and changes in the characteristics of the virus – which made the virus less prone to cause severe acute infections and may have reduced its ability to persist in the human body long enough to cause chronic disease.

Despite the decline in risk of developing long COVID, even a 3.5% risk is substantial. New and repeat COVID-19 infections translate into millions of new long COVID cases that add to an already staggering number of people suffering from this condition.

Estimates for the first year of the pandemic suggests that at least 65 million people globally have had long COVID. Along with a group of other leading scientists, my team will soon publish updated estimates of the global burden of long COVID and its impact on the global economy through 2023.

In addition, a major new report by the National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine details all the health effects that constitute long COVID. The report was commissioned by the Social Security Administration to understand the implications of long COVID on its disability benefits.

It concludes that long COVID is a complex chronic condition that can result in more than 200 health effects across multiple body systems. These include new onset or worsening:

- heart disease

- neurologic problems such as cognitive impairment, strokes and dysautonomia. This is a category of disorders that affect the body’s autonomic nervous system – nerves that regulate most of the body’s vital mechanisms such as blood pressure, heart rate and temperature.

- post-exertional malaise, a state of severe exhaustion that may happen after even minor activity — often leaving the patient unable to function for hours, days or weeks

- gastrointestinal disorders

- kidney disease

- metabolic disorders such as diabetes and hyperlipidemia, or a rise in bad cholesterol

- immune dysfunction

The National Academies report also concluded that long COVID can result in the inability to return to work or school; poor quality of life; diminished ability to perform activities of daily living; and decreased physical and cognitive function for months or years after the initial infection.

The report points out that many health effects of long COVID, such as post-exertional malaise and chronic fatigue, cognitive impairment and autonomic dysfunction, are not currently captured in the Social Security Administration’s Listing of Impairments, yet may significantly affect an individual’s ability to participate in work or school.

Many people experience long COVID symptoms for years following initial infection.

A long road ahead

What’s more, health problems resulting from COVID-19 can last years after the initial infection.A large study published in early 2024 showed that even people who had a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection still experienced new health problems related to COVID-19 in the third year after the initial infection.

Such findings parallel other research showing that the virus persists in various organ systems for months or years after COVID-19 infection. And research is showing that immune responses to the infection are still evident two to three years after a mild infection. Together, these studies may explain why a SARS-CoV-2 infection years ago could still cause new health problems long after the initial infection.

Important progress is also being made in understanding the pathways by which long COVID wreaks havoc on the body. Two preliminary studies from the U.S. and the Netherlands show that when researchers transfer auto-antibodies – antibodies generated by a person’s immune system that are directed at their own tissues and organs – from people with long COVID into healthy mice, the animals start to experience long COVID-like symptoms such as muscle weakness and poor balance.

These studies suggest that an abnormal immune response thought to be responsible for the generation of these auto-antibodies may underlie long COVID and that removing these auto-antibodies may hold promise as potential treatments.

An ongoing threat

Despite overwhelming evidence of the wide-ranging risks of COVID-19, a great deal of messaging suggests that it is no longer a threat to the public. Although there is no empirical evidence to back this up, this misinformation has permeated the public narrative.The data, however, tells a different story.

COVID-19 infections continue to outnumber flu cases and lead to more hospitalization and death than the flu. COVID-19 also leads to more serious long-term health problems. Trivializing COVID-19 as an inconsequential cold or equating it with the flu does not align with reality.

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,183

- 37,190

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #1,332

What’s the Risk of Getting Long COVID in 2024?

5 MINUTE READ

BY JAMIE DUCHARME

JULY 17, 2024 5:00 PM EDT

When researchers began studying Long COVID, after it became clear in 2020 that some people don’t recover from COVID-19 right away, some estimated that roughly a third of people who caught the virus experienced long-term symptoms.

But that was years ago, at a time before vaccines and endless iterations of Omicron, when most people had been infected once, if ever. How has the risk of contracting Long COVID changed over the years, as the virus has evolved and almost everyone in the U.S. has gotten vaccinated, infected, or both (sometimes many times over)?

Recent research offers promising signs that Long COVID is becoming less of a threat with time. But, experts say, there’s still reason for caution.

One study, published July 17 in the New England Journal of Medicine, tracked a steady decline in the incidence of Long COVID from 2020 to 2022. Among people in the study who got COVID-19 during the Delta era, 5.3% of those who were vaccinated and 9.5% of those who were unvaccinated had Long COVID symptoms a year later. Among people who got sick during the Omicron era, those numbers dropped to 3.5% and 7.8%.

Those findings, based on health records from almost 450,000 Department of Veterans Affairs patients who caught COVID-19, are “good news,” says study co-author Ziyad Al-Aly, a clinical epidemiologist at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “The risk of Long COVID after SARS-CoV-2 infection declined over the course of the pandemic.”

Read More: Why Are COVID-19 Cases Spiking Again?

It’s impossible to tell from the study whether risk has continued to decline with each Omicron subvariant that has emerged since 2022, but Al-Aly says his hunch is that it has. About 5% of U.S. adults say they currently have Long COVID, as of the latest Census Bureau estimate, down from more than 7% in the summer of 2022.

Vaccination, which previous research shows can protect against Long COVID, seems to be a major explanation for Long COVID’s decline—a good reason to keep current with shots as new ones come out, Al-Aly says. But the virus’ evolution and advancements in medical treatment, such as use of the antiviral Paxlovid, may have also contributed, he says.

Another recent study, published July 11 in Communications Medicine, suggests another possible factor. Reinfections—which account for an increasingly large share of COVID-19 cases, now that most people have already had the illness—may be less likely to result in Long COVID than primary infections. (Al-Aly's team did not assess the effect of reinfection in their paper.)

After analyzing health records from about 3 million people included in RECOVER, the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Long COVID research project, the researchers found that, in each era of the pandemic, Long COVID was diagnosed more frequently after first rather than second infections. “The initial results are promising,” says study co-author Emily Hadley, a research data scientist at the research nonprofit RTI International.

But, experts say, no one should dismiss reinfections as harmless. The study did not directly address a possibility that has been raised in some previous research, including some conducted by Al-Aly: that the risks of complications including heart, lung, and brain damage may pile up with each additional infection, whether or not someone is diagnosed with Long COVID.

Read More: COVID-Cautious Americans Feel Abandoned

“All studies that explore risks of reinfection should be through the lens of cumulative risk,” says David Putrino, who researches Long COVID at New York’s Mount Sinai health system but was not involved in either new study. Putrino also notes that health records—the basis of both new studies—are imperfect data sources, since they don’t capture the experiences of patients who don’t seek health care, nor those who are not officially diagnosed with Long COVID.

Even when focusing on people who were officially diagnosed with Long COVID, the new reinfections study still raises some alarms, says Dr. David Goff, a member of the NIH's RECOVER oversight committee. For him, the key takeaway isn’t that reinfections are less likely to result in Long COVID; it’s that some people still develop Long COVID, even after second infections.

“Even if you believe that the risk of developing Long COVID is a little less after a reinfection than after initial infection, it’s still there,” Goff says. “It’s not zero.”

Similarly, even in the best-case scenario in Al-Aly’s study—vaccinated adults who contracted COVID-19 during the Omicron era—more than 3% still ended up with Long COVID, which translates to potentially millions of new cases at a national level.

Taken together, the studies suggest that changes in the virus, population immunity, and medical care are chipping away at the risk of Long COVID, but not eliminating it completely. Whether one focuses on the good news or bad news depends largely on perspective and personal risk tolerance, says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist and Long COVID researcher from the Yale School of Medicine who was not involved in either new study.

Findings like these could be seen as reason to worry less. Or, they could be seen as proof that Long COVID—while perhaps not the threat it once was—continues to affect new people all the time. “Knowing how devastating Long COVID can be,” Iwasaki says, “I tend to be in the more cautious camp.”

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,183

- 37,190

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #1,333

Staying COVID-conscious is getting harder to do, advocates say that should change

Staying COVID-conscious is getting harder to do, advocates say that should change.

Staying COVID-conscious is getting harder to do, advocates say that should change

Even as Ottawa wastewater readings show a COVID-19 surge taking off in the city, keeping informed about COVID-19 is becoming harder.Get the latest from Elizabeth Payne straight to your inboxSign Up

Author of the article:

Elizabeth Payne

Published Jul 20, 2024 • Last updated 6 hours ago • 5 minute read

8 Comments

Article content

It was a familiar scene, but one that is becoming less common in Ottawa and across the country.On a recent Friday, people arriving for an outdoor concert and dance at Saw Gallery in downtown Ottawa were greeted with signs telling them that masks were mandatory. The same signs thanked them for supporting their community.

Participants happily complied. Some said they have continued to mask and seek out COVID-safe spaces since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. Others said they don’t always wear masks in public, but do so when there is a higher risk or they are protecting those who are more vulnerable.

“I am definitely here to throw my money at the organizers of masked events and also to be around the people who care about them,” said Tori Waugh who is a long-time fan of concert headliner Rae Spoon. The musician is immune compromised and requests masking and COVID safe policies at their concerts.

At a time when many people are trying to put COVID-19 behind them, some promoters and organizers continue to offer mandatory mask events to support artists and members of the public making efforts to stay COVID safe.

That includes Ottawa’s Gallery 101 on Catherine Street, which makes masks mandatory every second Saturday. “We have visitors who are elderly and there may be all sorts of people who have lower immune systems,” said gallery director and curator Laura Margita. “Since COVID is not going anywhere, it is up to us to try to keep ourselves and our artists and everyone else safe.”

But, even as Ottawa wastewater readings show a COVID-19 surge taking off in the city, part of a wave now spreading across North America, keeping informed about COVID-19 is becoming harder. That comes at a time when there is a growing body of evidence about a vast array of potential long-term risks from COVID-19 – including neurological and cardiovascular damage.

Advertisement 3

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Information about COVID-19 is less easily accessible than it once was and public health officials are less engaged in informing the public about those risks, said Dr. Joe Vipond, an Alberta emergency physician. He is among a group of concerned physicians and academics from across the country who created the not-for-profit Canadian Covid Society, in part, to fill in growing information gaps around COVID-19. On its website, the organization says it is committed to empowering people across Canada to protect their health and safety as COVID-19 continues to spread and evolve.

“We live in a society at the moment that has decided we can ignore COVID and, in fact, we should ignore COVID. We are told you do you and make your own risk predictions, but the information we need is not provided,” he said.

He noted that public health officials are seldom seen promoting masking or talking about the potential risks from COVID-19, the way they were earlier in the pandemic.

Increasingly, the data that tracks COVID infections is harder to find.

As of the end of this month, the Ontario government will stop funding the provincial wastewater surveillance program that has been a leader in tracking the virus that causes COVID-19 along with other infectious diseases, such as influenza and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus).

Advertisement 4

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

The provincial government says it is making the move to avoid duplication with the federal government, which is expanding its wastewater surveillance program. Researchers, health officials and others argue that the federal program will be significantly smaller than Ontario’s existing program and be less able to pinpoint timing and severity of COVID waves and other infectious diseases.

Last month, the Ottawa Board of Health directed the city’s Medical Officer of Health Dr. Vera Etches to write to provincial and federal partners to find ways to continue the wastewater testing that has been done at uOttawa since early in the pandemic. Meanwhile, some members of the public have started a petition to try to force the province to keep wastewater testing.

Rob Delatolla’s lab at uOttawa was the first in the country to identify the virus that cause COVID-19 in wastewater. It has continued to lead in the use of wastewater surveillance to better understand spread and risk of COVID-19 as well as other diseases.

Meanwhile, rapid antigen tests, which were once handed out by grocery stores and pharmacies across Ontario, are becoming harder to find.

Advertisement 5

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Organizers of the recent mandatory mask mandate concert at SAW Gallery had planned to have them on hand so people could test, but they had difficulty finding tests that were not expired.

Ottawa Public Health says the agency continues to make the tests available at selected locations — community clinics and neighbourhood health and wellness hubs. OPH will continue to offer the rapid antigen tests to the public “while provincial supplies last” said a spokesperson for public health.

More information is available at Ottawa Public Health.

Many individuals will have a difficult time knowing whether they have COVID-19, if they can’t access test kits.

There have been reports that people at high risk who qualify for the anti-viral treatment Paxlovid have had difficulty finding a pharmacy that stocks it.

Timely and up-to-date information about COVID-19 case counts and deaths are also more difficult to find, making it difficult to judge when the risk from COVID-19 is high in a community.

“A lot of things suggest to me that people are not being provided with the information they need in order to make informed decisions,” said Vipond.

Advertisement 6

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

Article content

Among other things, members of the Canadian Covid Society are advocating for a return to mandatory masking inside hospitals “because vulnerable patients shouldn’t be exposed to a virus unwittingly.” They are also pushing for clean air in schools to reduce spread among children.

Vipond noted that the Tour de France has recently made masks mandatory, during a pandemic wave in France.

“If you have worked your whole life to be in the Olympics or the Tour de France, the last thing you want is to be hit at the knees with a virus that eliminates you from competition or worse. Shouldn’t we expect the same for our patients? It boggles my mind that we have decided it is OK to infect susceptible people.”

Artist Rae Spoon, who was the force behind the mask mandatory concert at SAW Gallery said they bring an air filter to concerts and ask audience members and others on site to wear masks and take COVID-19 precautions. Spoon, who uses the pronouns they and them, was immune compromised after cancer treatment and continues to take precautions.

It is something many audience members appreciate, Spoon said.

“I have been pleasantly surprised by the support. During a tour in the Maritimes last spring, many people at shows told me they hadn’t been to an event since 2019 and were very grateful.”

Yommie

SpeedLimited

- Oct 2, 2013

- 64,183

- 37,190

- Country of Origin

- Country of Residence

- Thread starter

- #1,334

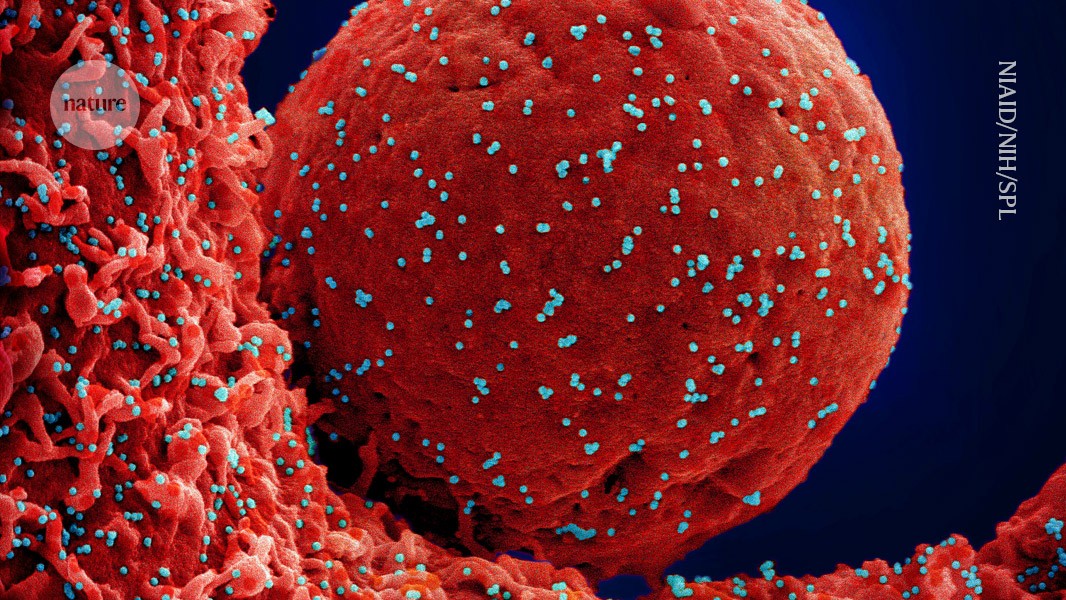

Long COVID lung damage linked to immune system response

Inhibiting a protein associated with chronic inflammation improves lung health in mice with COVID-19.

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

Pakistan Defence Latest

-

Iran has requested the Pakistan Air Force to provide training for its fighter pilots! (7 Viewers)

- Latest: muhammed45

-

-

-

GLORIOUS PAKISTAN "REVEALING RAWAT FORT | ARMY MUSEUM | MANKIALA STUPA" | PTV World (1 Viewer)

- Latest: Pakistan Ka Beta

-

Indian general praises professionalism of Pakistani peacekeepers in South Sudan (3 Viewers)

- Latest: WatchtowerWarrior4Ever

Country Watch Latest

-

-

-

-

Vice Chief of the Air Staff Air Marshal Amar Preet Singh appointed as the next Chief of the Air Staff of the Indian Air Force. (4 Viewers)

- Latest: TheChooChooTrain

-

Strategic Defense Options for Small Economies: How Can Bangladesh Effectively Defend Itself? (1 Viewer)

- Latest: Vikramaditya1

Latest Posts

-

-

'No work, no pay,' Samsung warns striking Indian workers as dispute escalates (19 Viewers)

- Latest: r3alist

-

-

Bengaluru To Manufacture India's First High-Speed Train, Designed For 280 Kmph For The Mumbai-Ahmedabad Corridor (5 Viewers)

- Latest: Beijingwalker

-