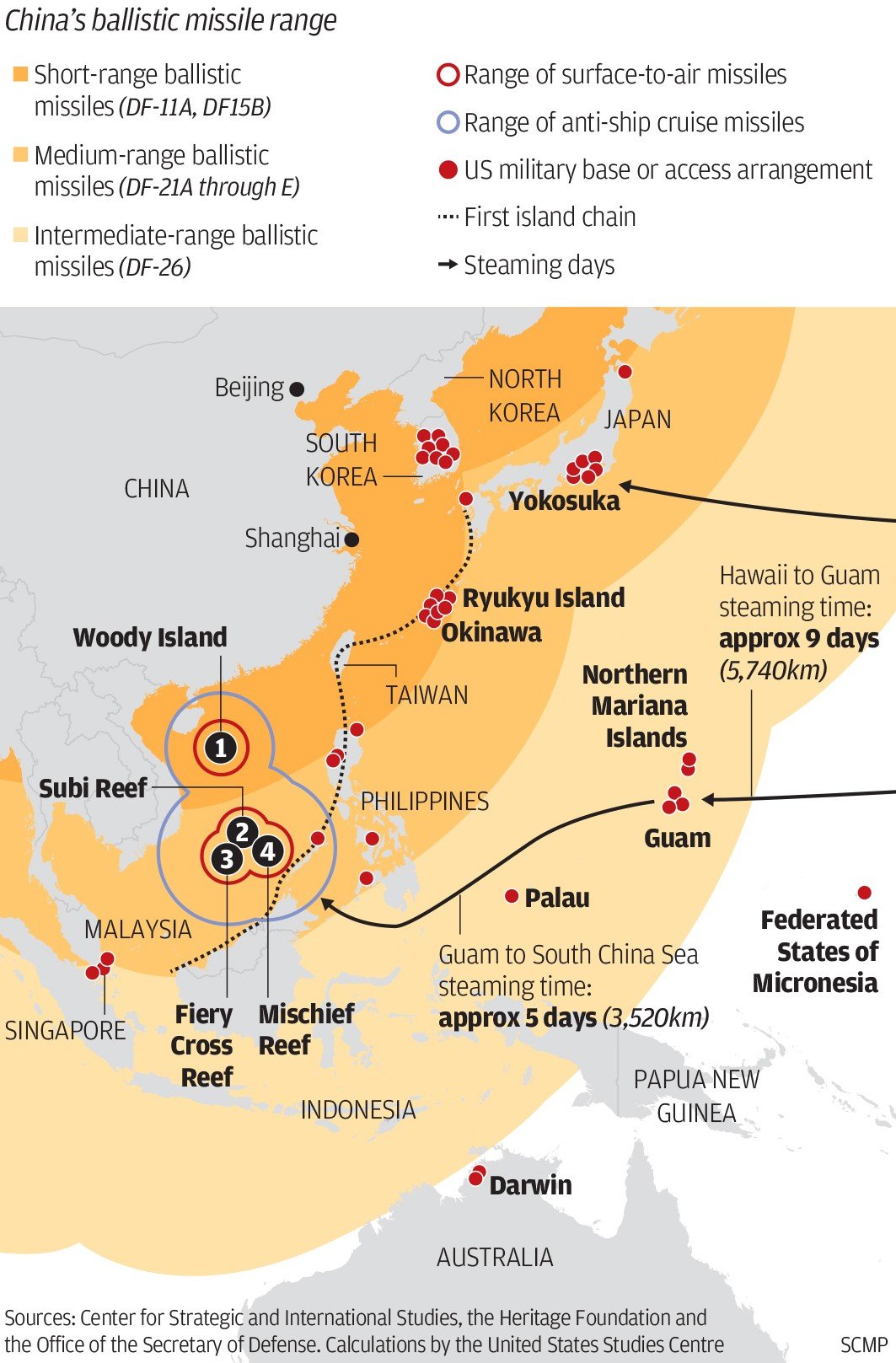

Are people simply forgetting that as China grows into a military superpower in the 2030s then it will start building bases in friendly countries like Pakistan?

China's current geographical vulnerability will be sorted in time as it reclaims Taiwan and starts building naval bases in friendly countries in Asia and Africa.

China's current geographical vulnerability will be sorted in time as it reclaims Taiwan and starts building naval bases in friendly countries in Asia and Africa.